Moray Place

This article grew out of an investigation of two early residents of 9 Moray Place, both of whom were file-cutters, and who appeared to be linked in some way. Read on to find out how.

The history of file-making

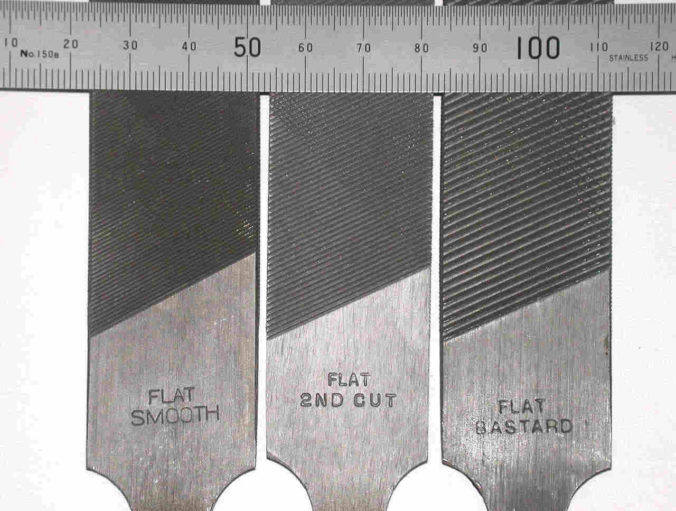

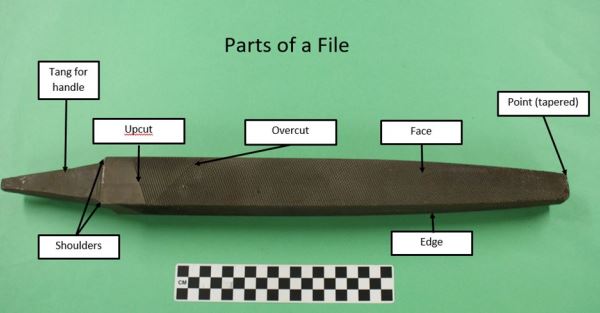

The file is an ancient tool with a crucial role in the development of industry. It is a piece of hardened steel with many small sharp teeth cut into its surfaces which can cut into, smooth, sharpen and shape any material.

Before the introduction of precision engineering of machine parts, files were important in putting together the mechanisms or working parts in items from watches to heavy engineering machinery. Component parts were roughly shaped by forging or casting, machined to an approximate size, then carefully filed to fit one another perfectly. Thus files were used by engineers and in all the metalworking trades; cutlers, silversmiths, clock and watchmakers, etc. There was also a large market for files for sharpening saw teeth. A type of file called a rasp was used in trades working with softer natural materials like wood, horn, marble and bone. Files were thus essential for the manufacture of most other items in factories, and were often one of the major tool costs in manufacturing. Worn files were often regrinded and re-cut to prolong their life .

Sheffield rules

In the UK, the centre of file-making was undoubtedly Sheffield. From 1624 the Cutler’s Company included file-making amongst the practices it covered, and exerted strict controls over the business, managing the apprenticeships and appointing Freemen. But when the Company’s control over the trades finally ended in 1814, the unions took its place, and worked hard to insist that any man in the trade must be a member of the union. Intimidation was common. In 1857, a saw grinder, James Lindley, was accused of taking on too many apprentices, and was followed for weeks and then shot and killed. Others were bombed out of their homes.

By the 1860s the file-cutters union had 6,000 members and no one manufactured files outside of Sheffield. However while all new files were bought from Sheffield firms, there was some scope for regrinding and re-cutting old files in other manufacturing centres, presumably by men who had been apprenticed in Sheffield.

Cutting a file

The creation of a file started with a bar of hard carbon steel, which was heated and forged into a round or flat bar, or whatever shape the file required. These were then softened by prolonged heating at constant temperature before being allowed to cool. These “blanks” could then be supplied to the file-cutters.

Blanks were first ground by hand on a sandstone grinding wheel to produce a perfect smooth surface.

Cutting was done by hand with a chisel and a special lump hammer. The blank was held by leather straps onto a lead bed on an anvil, the lead to protect the other side of the file. The craftsman would then work from the end towards the handle (tang), striking successive blows with the hammer on the chisel, to cut grooves in the file. A good file-cutter cut repeatedly at great speed, perhaps 80 blows per minute, such that they were known as “nicker-peckers”, local slang for a woodpecker.

For a double-cut file, the process was repeated on the same surface at a reverse angle. The file was then turned over and cut on the other side too.

Cutting a file with hammer and chisel. Credit: Hawley Collection, from Vom alten Handwerk, 1925-1931

Finally the file was hardened by coating in oil or paste to protect it, the paste sometimes being the waste ends from beer brewing, and then placing it in a bath of molten lead. After cooling in water and removing the paste, the files were then oiled, tested and wrapped and packaged for sale. Thus a file-cutter’s would require a number of employees, each working at one of the stages of production .

Machine cut files

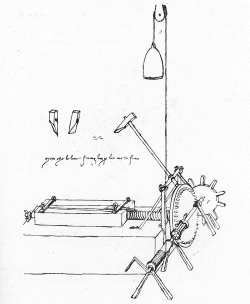

The first known proposal for a file cutting machine was by Leonardo da Vinci in 1505, though one was never built.

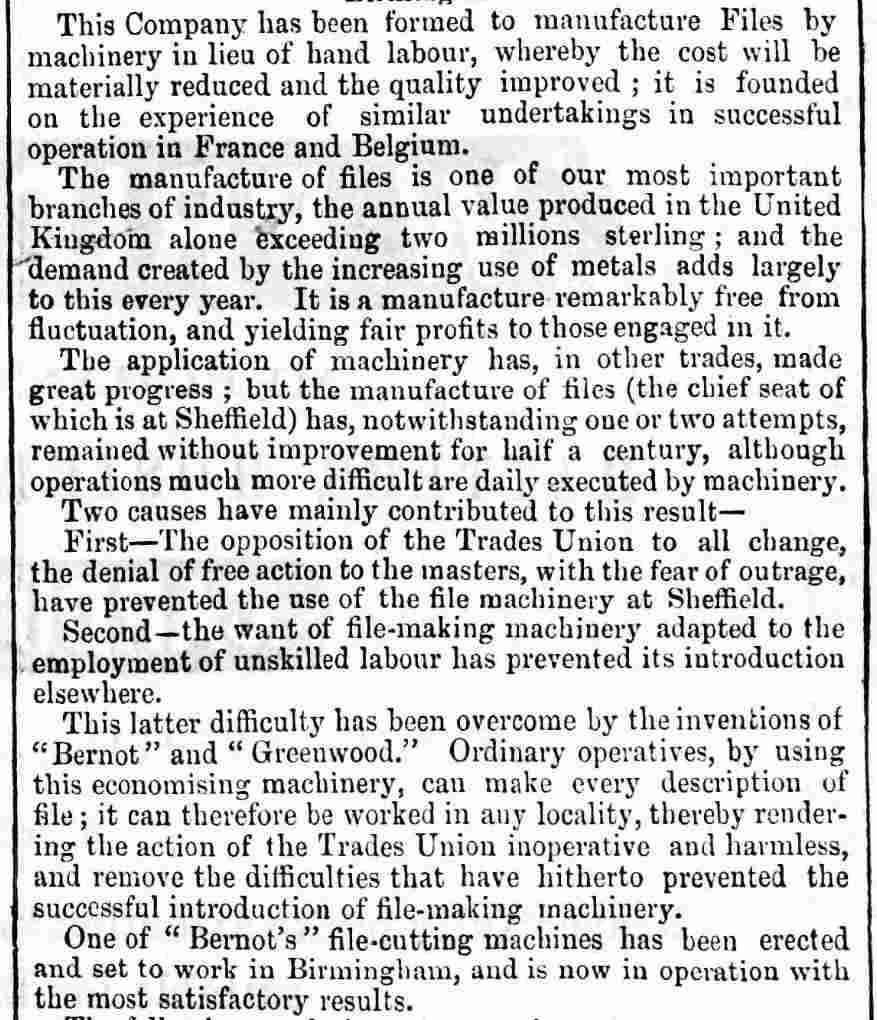

Serious attempts at mechanised file cutting started around the 1850s, with efforts initially outside Sheffield, away from the unions, and later in the city itself. Machines such as those by Frenchman E. Bernot were promoted with new companies such as the British Patent Hardware Company in Manchester, and the Patent File Company in Birmingham, but these companies generally failed due to inferior product or union opposition, or both. One reason for failure was that the machines’ perfect pattern of cuts led to grooves and chattering in use; the slight randomness of the human-made file actually proved an advantage in gaining a smooth finish, and the later and better machines attempted to reproduced this in their cutting.

Advert for launch of The Patent File Company, 1863. Cardiff & Merthyr Guardian July 1863. Credit: National Library of Wales

So much for the hype; in January 1867 the London Gazette reported the bankruptcy and winding up of The Patent File Company, less than four years later.

Nicholson in America produced one of the first successful machines in 1865, founding the Nicholson File Company of Providence, RI. Meanwhile in Sheffield an unusual for the time blinded trial was performed in 1866, using files machine-cut on one side, and hand-cut on the other, with the user unaware of which was which. This showed once and for all machine-cut files could equal or better those hand-made . Hand-cutting persisted into the 20th century, but eventually died out, while machine-cut file manufacture in the UK lasted in to the 1990s.

The Hetheringtons and Hendersons of Moray Place

The first two residents of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson’s newly built 9 Moray Place in Strathbungo were Thomas Nicholson of M Hetherington & Son, and then John Hetherington of R Hetherington & Co., both of them file-cutters. What was their role in the development of this trade, and how were they linked? With an understanding of the history of file manufacture, and a careful reconstruction of the families’ trees, we can begin to make some sense of the families’ involvement in file-cutting in Glasgow during the 19th century. It turns out these two firms were quite important; for starters in the Post Office Directory of 1855 there was only one other file-cutter listed in all Glasgow.

The Hetheringtons; four sons

John Hetherington and Elizabeth Wilson were both born around 1780 in Gateshead, and married c.1800. Over a period of 25 years from 1801 they had five sons, Robert Wilson Hetherington, William Hetherington, John Hetherington, Thomas Buttery Hetherington and Matthias Hetherington, and two daughters Elizabeth and Eleanor. The first two were born in Gateshead, after which the family moved to Old Monkland (i.e. the Coatbridge area) around 1808. John was a file-cutter who was in business in Scotland from around that time, and his sons followed him into the same trade. Given no files were made outside of Sheffield, they would likely have been grinding and recutting worn files for businesses in and around Glasgow. John appears to have died before the first census in 1841 however.

I can find no record of the middle brother John, who may have died young, but the careers of the other four can be traced to a degree.

William Hetherington, second brother (1806-1858), married Margaret Hallas from Birstall in Yorkshire, and they moved more than once between Glasgow and Sheffield. He died in Kinning Park in 1858 at the age of 52. His son, John Buttery Hetherington, born 1829, probably founded the firm JB Hetherington & Co, which first appeared in the Post Office Directory in 1856, but he died only a year after his father, in November 1859 at Crown Street, Hutchesontown. He was aged only 30, and curiously his wife Ann died only 6 weeks later, apparently childless. The company persisted for many years after, but no owner was listed in the PO Directories. In later years there were addresses listed in Rutherglen, and these were traced to one Andrew King, a power loom manufacturer. Andrew had married Elizabeth Hetherington, William’s sister and John B’s aunt, so presumably they inherited the business and continued it with some success.

Thomas Buttery Hetherington, the fourth brother (1815-1884), married Margaret Donnelly at a young age and had a family of nine. Another file-cutter, he also moved around. While his first children were born in Scotland, the last three were born in Cumberland, Newcastle and Yorkshire. By 1881 the couple had returned and were staying with their daughter Elizabeth and her Cairns family in Partick, but he appears to have been less successful in business, and sadly died in the Old Monkland Poorhouse in 1884, aged 69. His son Thomas married Harriet Swincoe from Sheffield, moved back to Glasgow, then after his father’s death settled again in Sheffield, also working as a file-cutter.

Robert Wilson Hetherington, the eldest brother (1801-1861), and Matthias Hetherington, his younger brother by 20 years (1821-1854), continued their father’s business together in Glasgow as R & M Hetherington. In 1846 the Glasgow Herald descibed in some graphic detail an accident at R & M Hetherington, when a brand new grindstone, five and a half feet diameter, weighing two tons, and running at 250 rpm, failed and struck its operator, Charles Mitchell, killing him instantly.

In January 1850 the London Gazette reported the bankruptcy of the business.

Matthias, undaunted, formed M Hetherington & Co in Dale Street, Tradeston, and entered for the first time into the practice of cutting new files outside of Sheffield, but he died young in 1854.

Matthias had married Margaret Crawford Henderson (1819-1014) in 1842 in the Gorbals, and had four children. His two daughters, Marian and Elizabeth, married. John Henderson Hetherington married, and forgoing the business of file-cutting, went successfully into the yarn trade, while Matthias WIlson Hetherington died at the age of 10. The children were still young when Matthias died in 1854, aged only 33, so there was no obvious successor to the business. Ownership appeared to move to Matthias’ brother-in-law, his wife’s younger brother, Thomas Henderson (1821-1872), who was also a file-cutter. Thomas, although from a Gorbals family, was living and working in Sheffield at the time and appears to have moved back to Glasgow with his family to take over the business on Matthias’ death, and moved in to 69 Abbotsford Place in the Gorbals.

Thomas Henderson – Experiments in machine-cut files

Thomas appears to have led the business in a new direction. At this point the firm was already the first to make files in Scotland, and to make its own blanks, and no one had yet introduced machinery to the trade. In 1855 the Glasgow Herald reported the invention of a new file-cutting machine by a Mr Ross, of Glasgow business Ross & Young, with some excitement.

By May 1856, M Hetherington were advertising machine-cut files using Ross’ machines.

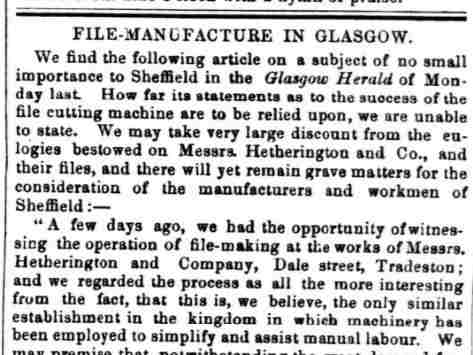

Then in December 1856 an extensive article described a visit to M Hetherington & Co, who had first installed Ross’ machines in September 1855. The article described how the workforce had objected, and in October the Secretary of the Union travelled from Sheffield to Glasgow, and marched the entire disgruntled workforce the short distance to the steamer to Liverpool, en route back to Sheffield! This brought the works to a close for three months. Nonetheless the business got going again with new labour and claimed to be the first enterprise anywhere, and certainly outside Sheffield, to be machine-cutting files, with excellent results and cost savings.

The article was received in Sheffield with some alarm, and it was reproduced in the Sheffield Independent in its entirety, but with a slightly disbelieving introduction.

The enterprise appears to have been a success initially, and Thomas purchased the newly built 9 Moray Place with the proceeds in 1862. However, as we have noted, the first experiments in machine cutting were not ultimately successful, and in November 1862 M Hetherington, and Thomas Henderson, its sole partner, went bust. He sold Moray Place and moved to Winton Terrace in Shettleston, and probably died there in 1872.

R Hetherington & Son

Robert and Matthias’ business R & M Hetherington had gone bust in 1850, but Robert wasn’t finished either. He had married Catherine (Cruikshanks?) in 1820 and had two boys, John and Robert, and daughters Elizabeth & Cathrine. He married again in 1847 to Elizabeth Massey of Nottingham, and had a further daughter Mary. Immediately after the failure of R & M Hetherington he founded R Hetherington & Son with his son John at 8 Surrey Lane in the Gorbals, while living in nearby Cavendish Street. His other son Robert was also a file-cutter, but I couldn’t find him after 1841.

John (b.1822) had married Marian McDonald Henderson in 1847 and they lived in South Apsley Place in the Gorbals. Marion was the sister of Margaret Henderson, who had married John’s uncle Matthias (note Matthias was only one year older than John). She was of course also the sister of Thomas Henderson, the owner of M Hetherington & Co. When Robert died in 1861 in Kinning Park, John continued the business. When Thomas’ business failed the following year, he sold or gave 9 Moray Place to his sister Marion and brother-in-law John shortly after.

They only stayed a few years however; sometime around 1868 they moved to Dundas Cottage, next to the factory in Tradeston. John died in 1871 aged 49 and his son, Robert Wilson Hetherington (1850-1925) continued the business. Robert never married, but lived with his mother and two sisters in Kenmure Street, Pollokshields. His brother John Henderson Hetherington went into shoe manufacturing instead.

Epilogue

Both JB Hetherington, under Andrew King, and R Hetherington & Son, under Robert Wilson Hetherington, prospered and continued in business beyond 1890.

And there you have it, the history of file-making in Glasgow, and the first attempt to break Sheffield’s monopoly and mechanise the industry. Men versus machines, bosses versus unions, boom and bust, family rivalries and alliances, one family summarising all that was the industrial revolution.

Additions and corrections are welcome.

April 5, 2022 at 9:29 am

Fascinating reading 👍

A great insight into Old Glasgow

The people and the buildings