I’m no Indiana Jones. And I’m not an archaeologist either. But I think I’ve solved an archaeological mystery.

The Camphill fort is a large circular earthwork atop Queen’s Park, almost 100m in diameter. The rampart is now much eroded, and the surrounding ditch has been filled in for a road or path, but it would have been a substantial structure in its day. For years archaeologists have pondered its origins.

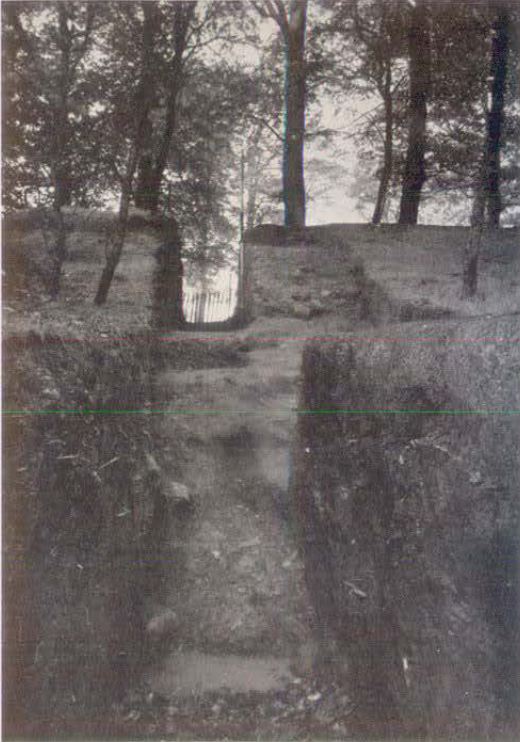

View of the Camphill earthworks by Duncan Brown, 1890s. Source: GlasgowStory

The same view, I think, in December 2024. Contours have changed slightly, and the trees and fences are different. The earthwork appears more eroded. Looking north, with the allotments to the right.

It is thought likely to be an iron-age fort of some type, but other suggestions include a Roman fort and a medieval castle.

Also puzzling are the large stones or boulders that lie somewhat incongruously within the fort. There are twenty or more of them, with the largest forming a small ring, these days used as an informal fireplace. Suggestions for these include a stone circle, a military position in the Battle of Langside

The stones of Camphill Fort

Archaeologist Kenny Brophy describes the site well in his Urban Prehistorian blog post

Excavations

Archaelogical digs were undertaken in 1867, and again in 1951.

In 1867 the family of the late Neale Thomson of Camphill House decided to investigate the camp, and instructed the estate overseer, Mr Hamilton, to explore further. The excavations were reported in the Herald on 15 July 1867 and revealed a “sort of paved floor” near the centre of the enclosure, at a depth of about 8 feet (2.5 m). Over the surface lay a cake of charred oats mixed with fragments of oak, samples of which were at one time displayed in the People’s Palace. This was thought to be a grain-drying kiln, but they were no wiser regarding its age. They made no mention of the stones.

Photographs from the 1890s and 1920s suggest the earthworks were fenced off for protection in the park’s early years.

A 1921 view of the earthworks, which were initially fenced off for protection. Source: GlasgowStory/Mitchell Library

Excavations carried out by Fairhurst and Scott in July and September 1951 recovered sherds of pottery “not later than 14th century” from the very bottom of the ditch. They concluded that the earthwork is best described as a “clay castle”

Section across ditch and rampart from outside, 1951. Source: Fairhurst & Scott, 1953

There were further assessments in 1973 by EJ Talbot

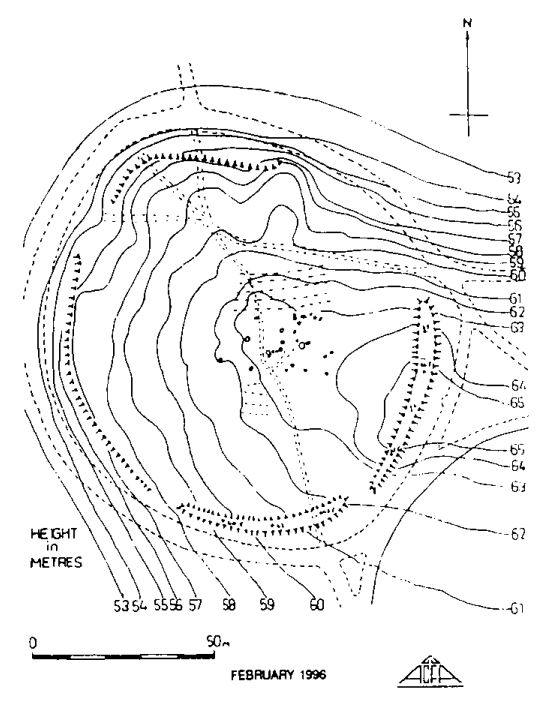

Site map with contours from the 1996 survey, showing how the fort sits on the western slope rather than on the top of the hill. Source: Council for Scottish Archaeology

So what’s the truth?

What type of fort was it? I have no idea. But I have discovered the origin of the boulders within it, and can now reveal all.

They were dumped there by the council.

And so Fairhurst and Scott’s “landscape gardening craze” theory was pretty spot on.

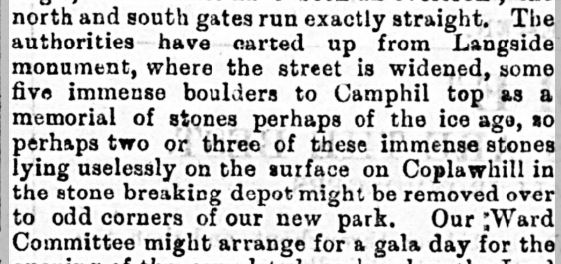

A letter to the editor of The Southern Press on 27 April 1895 suggesting improvements to the proposed Govanhill Park notes that “the authorities have carted up from Langside Monument, where the street is widened, some five immense boulders to Camphill top as a memorial of stones perhaps of the ice age…” and suggests they do something similar in Govanhill

Except from letter in Southern Press, 27 Apr 1895. Source: BNA

The council had acquired Camphill House and its surrounding land in 1894 to enlarge Queen’s Park, thus opening the fort to the public for the first time. They set about demolishing the stone wall around the estate and replacing it with iron railings, and converted the house to a costume museum. As part of the plans to install the railings up towards Langside Mounument, the council approved a road widening scheme on Langside Avenue in January of 1895. This was just prior to the construction of the new free church on Battle Place (The Church on the Hill) which commenced in September and the Church elders gave up some of their plot to assist in this. I presume the boulders were left over from these road works. It is even possible it is these works that are evident in Duncan Brown’s 1890s photograph of the old Langside Village.

Duncan Brown’s 1890’s photograph of Algie Street, old Langside Village, with Battlefield Monument behind. The Church on the Hill would be built on the left. Are these the 1895 roadworks that supplied the boulders? Source: GlasgowStory

The installation of the boulders inspired other letter writers that year; one suggested installing in the camp some sections of a recently felled huge willow at Crossmyloof, while another suggested carving out the recently discovered underground cave dwelling in Minard Road and re-installing it in the camp, thus saving it from destruction by the new tenements.

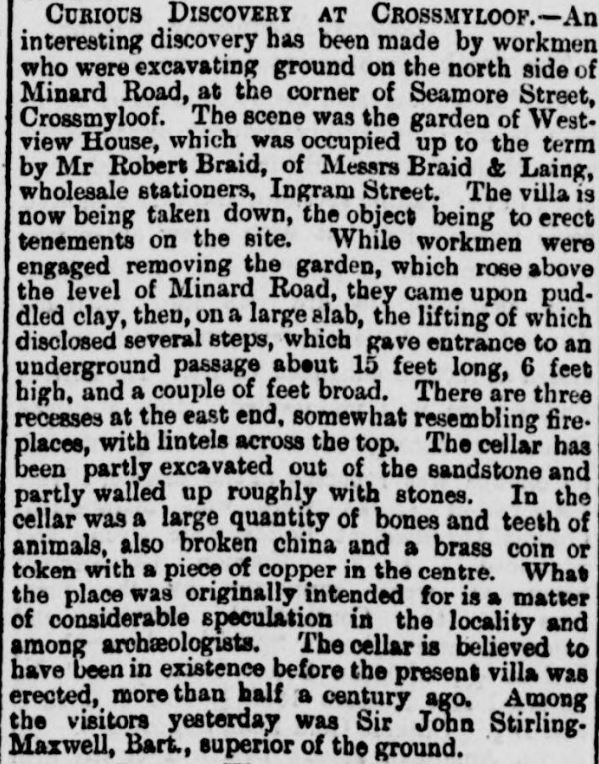

The Minard Road Cave

Yes, there really was a secret underground chamber in Minard Road. It was discovered under the garden of West View House, then being demolished for tenements, and had been partially carved out of the sandstone. The house was in Seymour Road, now better known as Waverley Street, and the location of the garden puts the find at about 30-36 Minard Road. The discovery was well described in the Herald

Its fate is unknown, it might even still be there

Description of the discovery in Minard Road, in the garden of West View House, Seamore (sic) Street, now Waverley Street. Source: Glasgow Herald 20 Jun 1895 / BNA

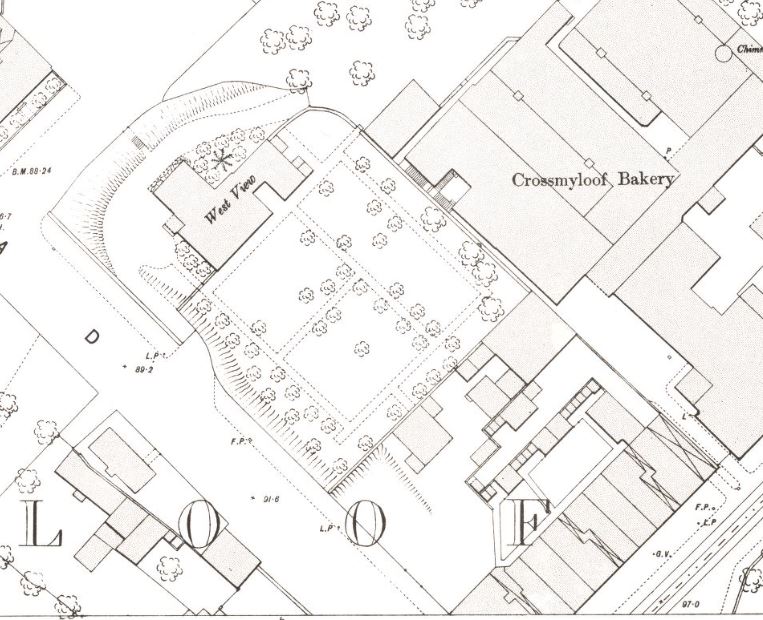

Location of West View House and garden on OS Town Map of 1893. Source: NLS Maps

Incidentally, the council also proposed that same summer to erect two back-to-back rows of tenements in the park, on Pollokshaws Road from Langside Avenue north towards the current pond. Fortunately this did not proceed and this part of the park survived. They later moved the National Bank of Scotland building stone by stone from Queen Street to the corner of this plot, and opened it as Langside Halls on Christmas Eve 1903.

And one final irony. The council website still supports the theory the stones are remnants of the Battle of Langside, even though they put them there themselves

References

{3557955:755CCSNB};{3557955:ZLCS9PU2};{3557955:8XTQM4P9};{3557955:AY57JAKP};{3557955:73UQQW6C};{3557955:ZLCS9PU2},{3557955:DWWGSAXN};{3557955:ZLCS9PU2},{3557955:V35ZQQ8M};{3557955:ZLCS9PU2};{3557955:LMBSCBGX};{3557955:ATXUXJCG};{3557955:TESYC8IE};{3557955:XI3HJ57S};{3557955:4TPY4IYL};{3557955:WHXCAM8N}

vancouver

asc

0

5050

%7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3A%22zotpress-098449739c5d28ef3e6be816e1a7a069%22%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%22ATXUXJCG%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221999%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EDiscovery%20and%20Excavation%20in%20Scotland%201999%20%5BInternet%5D.%20Council%20for%20Scottish%20Archaeology%3B%201999%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%206%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.archaeologyscotland.org.uk%5C%2Fwp-content%5C%2Fuploads%5C%2F2022%5C%2F05%5C%2F1999.pdf%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.archaeologyscotland.org.uk%5C%2Fwp-content%5C%2Fuploads%5C%2F2022%5C%2F05%5C%2F1999.pdf%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22document%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Discovery%20and%20Excavation%20in%20Scotland%201999%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221999%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.archaeologyscotland.org.uk%5C%2Fwp-content%5C%2Fuploads%5C%2F2022%5C%2F05%5C%2F1999.pdf%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-06T11%3A57%3A21Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22LMBSCBGX%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221996%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EDiscovery%20and%20Excavation%20in%20Scotland%201996%20%5BInternet%5D.%20Council%20for%20Scottish%20Archaeology%3B%201996%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%206%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.archaeologyscotland.org.uk%5C%2Fwp-content%5C%2Fuploads%5C%2F2022%5C%2F05%5C%2F1996.pdf%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.archaeologyscotland.org.uk%5C%2Fwp-content%5C%2Fuploads%5C%2F2022%5C%2F05%5C%2F1996.pdf%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22document%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Discovery%20and%20Excavation%20in%20Scotland%201996%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221996%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.archaeologyscotland.org.uk%5C%2Fwp-content%5C%2Fuploads%5C%2F2022%5C%2F05%5C%2F1996.pdf%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-06T11%3A55%3A58Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%228XTQM4P9%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Thomas%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222008-05-23%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EThomas%20MM.%20The%20Devil%26%23x2019%3Bs%20Plantation.%202008%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%204%5D.%20Trip%20Eight%3A%20The%20Iron%20Age.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.elementalfilms.eu%5C%2Fdevilsplantation%5C%2Fthe-iron-age%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.elementalfilms.eu%5C%2Fdevilsplantation%5C%2Fthe-iron-age%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Trip%20Eight%3A%20The%20Iron%20Age%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Mary%20Miles%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Thomas%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20days%20are%20longer%20if%20not%20always%20lighter.%20After%20months%20of%20domestic%20upheaval%2C%20in%20late%20April%20I%20return%20to%20live%20in%20Glasgow%20after%20four%20years%20in%20Edinburgh.%20If%20nothing%20else%20the%20move%20makes%20gathering%20material%20for%20this%20project%20less%20arduous.%20Now%20based%20in%20the%20city%5Cu2019s%20southside%2C%20I%5Cu2019m%20close%20to%20several%20of%20the%20places%20I%5Cu2019m%20recording%20for%20the%20Devil%5Cu2019s%20Plantation%20website%2C%20the%20closest%20being%20the%20Camphill%20Earthworks%2C%20claimed%20to%20be%20an%20Iron-Age%20site%20and%20a%20major%20hub%20in%20Harry%20Bell%5Cu2019s%20Secret%20Geometry%20of%20Glasgow.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222008-05-23T16%3A03%3A43%2B00%3A00%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.elementalfilms.eu%5C%2Fdevilsplantation%5C%2Fthe-iron-age%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en-GB%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-04T10%3A51%3A58Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22WHXCAM8N%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EGlasgow%20City%20Council%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%204%5D.%20Queen%26%23x2019%3Bs%20Park.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.glasgow.gov.uk%5C%2Farticle%5C%2F4189%5C%2FQueen-s-Park%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.glasgow.gov.uk%5C%2Farticle%5C%2F4189%5C%2FQueen-s-Park%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Queen%27s%20Park%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.glasgow.gov.uk%5C%2Farticle%5C%2F4189%5C%2FQueen-s-Park%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-04T09%3A54%3A06Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%224TPY4IYL%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EGlasgow%2C%20Crossmyloof%20%7C%20Canmore%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcanmore.org.uk%5C%2Fsite%5C%2F44295%5C%2Fglasgow-crossmyloof%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcanmore.org.uk%5C%2Fsite%5C%2F44295%5C%2Fglasgow-crossmyloof%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Glasgow%2C%20Crossmyloof%20%7C%20Canmore%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcanmore.org.uk%5C%2Fsite%5C%2F44295%5C%2Fglasgow-crossmyloof%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T17%3A36%3A58Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22XI3HJ57S%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221895-06-20%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ECurious%20Discovery%20at%20Crossmyloof.%20Glasgow%20Herald%20%5BInternet%5D.%201895%20Jun%2020%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18950620%5C%2F008%5C%2F0004%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18950620%5C%2F008%5C%2F0004%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Curious%20Discovery%20at%20Crossmyloof%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2220%20Jun%201895%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18950620%5C%2F008%5C%2F0004%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T17%3A36%3A17Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22TESYC8IE%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221895-04-27%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EThe%20Govanhill%20New%20Park.%20Southern%20Press%20%28Glasgow%29%20%5BInternet%5D.%201895%20Apr%2027%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2FBL%5C%2F0001844%5C%2F18950427%5C%2F034%5C%2F0004%3Fbrowse%3DFalse%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2FBL%5C%2F0001844%5C%2F18950427%5C%2F034%5C%2F0004%3Fbrowse%3DFalse%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Govanhill%20New%20Park%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2227%20Apr%201895%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2FBL%5C%2F0001844%5C%2F18950427%5C%2F034%5C%2F0004%3Fbrowse%3DFalse%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T16%3A30%3A33Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22755CCSNB%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EGeograph%3A%20Queens%20Park%20stone%20circle%20%26%23xA9%3B%20Thomas%20Nugent%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.geograph.org.uk%5C%2Fphoto%5C%2F2540319%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.geograph.org.uk%5C%2Fphoto%5C%2F2540319%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Geograph%3A%20Queens%20Park%20stone%20circle%20%5Cu00a9%20Thomas%20Nugent%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22At%20the%20high%20point%20in%20the%20park%2C%20these%20stones%20are%20believed%20to%20be%20the%20remnants%20of%20a%20encampment%20which%20formed%20an%20important%20military%20position%20in%20connection%20with%20the%20nearby%20Battle%20of%20Langside%20in%201568%20http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fen.wikipedia.org%5C%2Fwiki%5C%2FBattle_of_Langside%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.geograph.org.uk%5C%2Fphoto%5C%2F2540319%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T16%3A24%3A46Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22DWWGSAXN%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221867-07-15%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EInteresting%20Discovery%20At%20Camphill.%20Glasgow%20Herald%20%5BInternet%5D.%201867%20Jul%2015%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18670715%5C%2F014%5C%2F0004%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18670715%5C%2F014%5C%2F0004%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Interesting%20Discovery%20At%20Camphill%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2215%20Jul%201867%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18670715%5C%2F014%5C%2F0004%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T15%3A47%3A30Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22V35ZQQ8M%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Fairhurst%20and%20Scott%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221953-11-30%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EFairhurst%20H%2C%20Scott%20JG.%20The%20Earthwork%20at%20Camphill%20in%20Glasgow.%20Proceedings%20of%20the%20Society%20of%20Antiquaries%20of%20Scotland%20%5BInternet%5D.%201953%20Nov%2030%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D%3B85%3A146%26%23x2013%3B57.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjournals.socantscot.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fpsas%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F8389%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjournals.socantscot.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fpsas%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F8389%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Earthwork%20at%20Camphill%20in%20Glasgow%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Horace%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Fairhurst%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22J.%20G.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Scott%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%26nbsp%3B%26nbsp%3B%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221953-11-30%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.9750%5C%2FPSAS.085.146.157%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%222056-743X%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjournals.socantscot.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fpsas%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F8389%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T15%3A14%3A38Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22ZLCS9PU2%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EGlasgow%2C%20Queen%26%23x2019%3Bs%20Park%2C%20General%20%7C%20Canmore%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcanmore.org.uk%5C%2Fsite%5C%2F168587%5C%2Fglasgow-queens-park-general%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcanmore.org.uk%5C%2Fsite%5C%2F168587%5C%2Fglasgow-queens-park-general%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Glasgow%2C%20Queen%27s%20Park%2C%20General%20%7C%20Canmore%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fcanmore.org.uk%5C%2Fsite%5C%2F168587%5C%2Fglasgow-queens-park-general%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T11%3A31%3A34Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22AY57JAKP%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Brophy%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017-09-15%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EBrophy%20K.%20the%20urban%20prehistorian.%202017%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D.%20Psychogeography%20in%20the%20park.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Ftheurbanprehistorian.wordpress.com%5C%2F2017%5C%2F09%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Ftheurbanprehistorian.wordpress.com%5C%2F2017%5C%2F09%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Psychogeography%20in%20the%20park%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Kenneth%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Brophy%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%221%20post%20published%20by%20balfarg%20during%20September%202017%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222017-09-15%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Ftheurbanprehistorian.wordpress.com%5C%2F2017%5C%2F09%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T11%3A30%3A49Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%2273UQQW6C%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EGreater%20Govanhill%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Dec%203%5D.%20Digging%20into%20the%20History%20of%20Queen%26%23x2019%3Bs%20Park.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.greatergovanhill.com%5C%2Flatest%5C%2Fdigging-into-the-history-of-queens-park%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.greatergovanhill.com%5C%2Flatest%5C%2Fdigging-into-the-history-of-queens-park%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Digging%20into%20the%20History%20of%20Queen%5Cu2019s%20Park%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Queen%5Cu2019s%20Park%20has%20stirred%20the%20interest%20of%20historians%20and%20archeologists%20for%20a%20long%20time.%20In%20this%20article%2C%20Ken%20McElroy%20explores%20the%20fascinating%20history%20of%20how%20the%20popular%20space%20has%20been%20used%20over%20time%20by%20digging%20beneath%20the%20surface.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.greatergovanhill.com%5C%2Flatest%5C%2Fdigging-into-the-history-of-queens-park%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en-US%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-12-03T11%3A28%3A42Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D

Like this: Like Loading...

December 7, 2024 at 10:15 am

Excelled yourself this time Andrew, fascinating. I will pay a bit more attention next time I walk though the park.