The story of the former inhabitants of 24 Moray Place wanders amongst sugar refining, Britain’s first diesel engine, the curious origins of a famous Irish song, the dangers of Australian bushrangers, the origin of Scottish turntable ferries, Confederate gun-running, the loss of the SS Atlantic, an episode of Taggart and more.

Robert Andrew Robertson

The first occupant of 24 Moray Place, from 1874 to 1876, was Robert Andrew Robertson, an engineer.

Robert was born to Andrew Robertson and Isabella Riddell. His father was from Kelso, but moved to London. At the time of Robert’s birth on 23 April 1843 Andrew was working at Islington Preparatory School as the arithmetical and writing master.

Robert was baptised at the National Scotch Church (“The Caledonian Church”) in Regent Square, just two weeks after the Great Disruption of 1943 that saw the Free Church including, I think, this London congregation, split from the Church of Scotland.

Robertson appears to have been known professionally as “R.A.” or Andrew, rather than Robert. I have used “R.A.” to avoid confusion with his father and son, both Andrew Robertson.

He served his apprenticeship with Messrs. James Simpson & Co., pump manufacturers of Pimlico. In 1864 the manager there, David Thomson, took him to South Staffordshire Waterworks in Lichfield, where he carried out some extensive tunnelling operations to supply the expanding Black Country industries and population with fresh water .

From 1866 to 1872 he was Manager, for Mr James Duncan of Greenock, of the Clyde Wharf Sugar Refinery in London, where he developed his extensive knowledge of the handling of sugar which would serve him well in later years. The refinery was ultimately not a huge success, going bankrupt in 1886 and later burning down, but it was the first of several that developed in Silvertown, East London. The Tate & Lyle refinery still operates there to this day .

He was elected an Associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers on 2 March 1869, and elevated to Member on 14 May 1878.

He married Elizabeth Ritter of Melbourne, Australia, in 1870 in Greenwich.

Around 1874 R.A. moved to Glasgow to take up a post at Mirrlees, Tait & Watson, and for a short period settled at 24 Moray Place. He already had five children and within three years he moved to 42 Aytoun Road in Pollokshields, and later as his success continued, to Park Circus. He would ultimately have at least 12 children.

Mirrlees, Watson & Co

In 1885 he became a partner in the firm, now Mirrlees, Watson & Co. The company was based at Scotland Street Ironworks, and was a manufacturer of sugar refining equipment which it exported around the world. At one point it was estimated to have 80% of the world market.

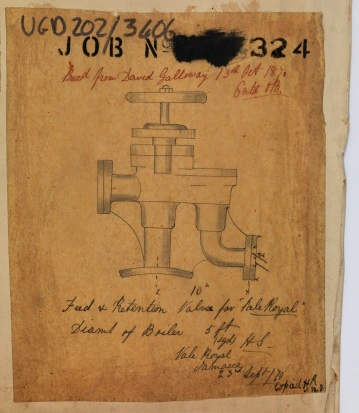

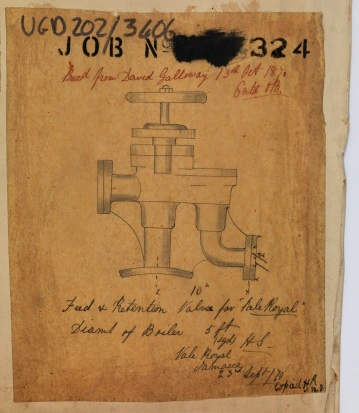

Technical drawing of a Mirrlees Watson feed and retention valve, 1870

Source: University of Glasgow Archives

The Mirrlees Watson Ironworks at 45 Scotland Street, 1967. The building to the right survives as Murgitroyd & Co. Source: Prof John Hume, Canmore. (The original on Canmore is inadvertently reversed.)

The site now, Carnoustie Place Industrial Estate. The ironworks are long gone. Source: Streetview

While the British Empire had by this time banned slavery, many countries with which the company dealt had not, and plantation workers remained poorly treated. It is difficult to judge what Robertson’s views were, but he would have been well aware of plantation conditions, as he regularly travelled to sites of sugar production all around the world as part of his work .

In 1868 the business had acquired the rights to American David Weston’s centrifuge for separating sugar from molasses, and in 1883 spun off a new company, Watson, Laidlaw & Co, to manufacture these. The firm was based in Dundas Street. R.A.’s son, Andrew Robert, having studied at Glasgow and then MIT in Boston, worked there as a draughtsman and in 1897 became manager.

In 1887 they acquired patents for evaporating apparatus useful to the sugar industry from Homer T Yaryan, a talented and prolific Toledo inventor, and in 1889 the firm became Mirrlees, Watson, Yaryan & Co.

There is a fuller contemporary description of the business in Local Industries of Glasgow and the West of Scotland .

Diesel power

Rudolf Diesel was a German engineer who devised and promoted the idea of the diesel engine. He began building prototypes from 1893, but his first prototype failed. Redesigned into his second, it ran briefly to become the world’s first functioning diesel engine in 1894, but was problematic. In October 1896 his third version achieved notable success. R.A. Robertson was aware of this new work, being advised by Lord Kelvin, and put a motion to his board to investigate the new invention. Its first public test was on 17 February 1897. So on the very next day, the 18th, Watson, Robertson and Platt arrived for a three day observation of the new engine, and began negotiations to secure an exclusive overseas licence, signed on 23 March .

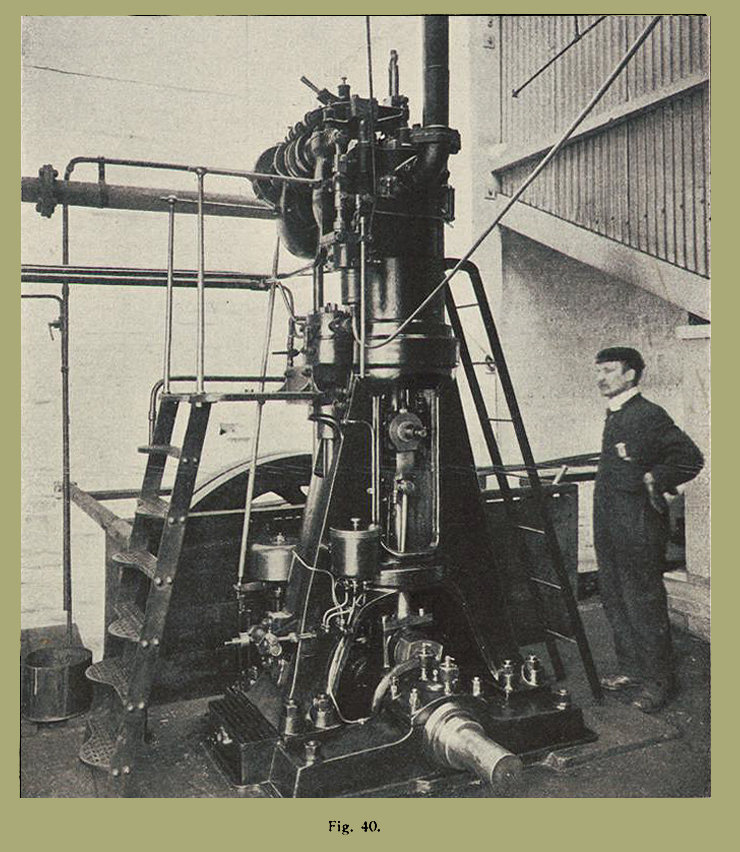

Returning home, they built a copy according to Diesel’s drawings, completed in November, and thus created the world’s third functioning diesel engine in Glasgow, or as Diesel himself described it, “the first English machine”. Oops. This engine ran for many years, and now resides in the Anson Engine Museum in Poynton, Cheshire.

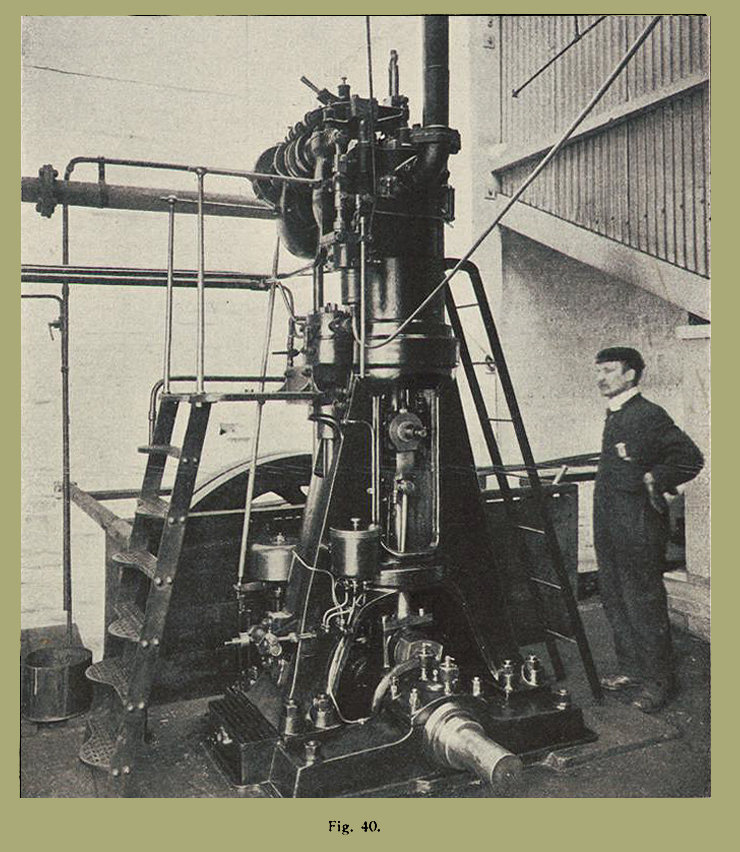

The world’s third diesel engine, Britain’s first, seen still operating in June 1912. Source: Augsburg University of Applied Sciences

While the company appear to have found the diesel engines a distraction and released their exclusive licence, the diesel business did eventually prosper as a separate company manufacturing industrial and marine diesels in Stockport until very recently, as Mirrlees, Bickerton & Day, latterly Mirrlees Blackstone. They were bought out by MAN of Augsburg, and closed down in 2006.

In 1900 R.A. set out on one of his many overseas business trips, leaving Southampton on the SS Pfalz for Buenos Aires. On 2 June in the Bay of Biscay he died suddenly of apoplexy (a stroke). He is buried in the English Cemetery, La Coruña, Galicia, Spain.

His obituary noted “His private correspondence was extensive and his advice much sought, but his great modesty of character prevented him from seeking the public recognition which his capacities and labour might have obtained.”

The Ritters

R.A.’s wife Elizabeth has a curious family history. Her father Edward Frederick Christian Ritter was born in Breslau, Prussia (now Wrocław, Poland) in 1817. He noted his father as Frederick Christian Ritter, apparently a Prussian officer who found himself in France in the aftermath of Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, while his mother was the officer’s French mistress or wife.

He obtained a PhD in Bonn before moving to London in the 1840s, where he taught music and French. Notably, he was a colleague of R.A. Robertson’s father Andrew at Islington Preparatory School.

Around 1848 he moved to Limavady, near Londonderry, to tutor in music the two daughters of a local prominent landowner, John Alexander. Somewhat unprofessionally, he found himself rather attracted to his younger pupil Jane, who at 20 was 17 years his junior. Unsurprisingly, her father did not approve, so they eloped to London to be married. Her older sister Anna had her back though, and was a witness at the marriage. The couple then fled further, to Australia, where he achieved success as a gold trader. He returned to London after five years, and presumably reconnected with his fellow teacher Andrew Robertson, as Andrew’s son Robert and the Ritter’s Australian-born daughter Elizabeth were married in Greenwich 15 years later.

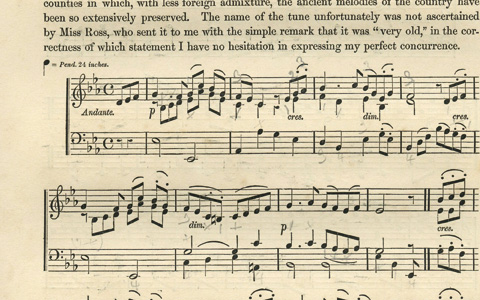

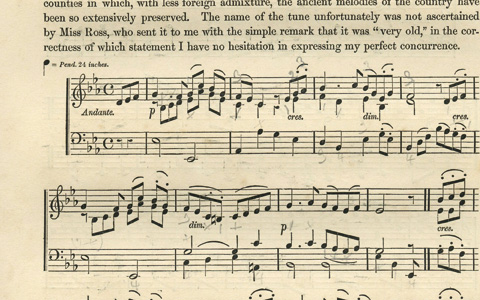

Brendan Drummond, writing in the Journal of Music, has proposed an interesting theory. He suggests during his time teaching music in Limavady Edward Ritter was responsible for modernising an old Irish tune that had been overheard in the mountains by a Limavady resident and family friend, Jane Ross. She passed the song to a collector of such tunes without specifying how she came about it. The collector published it, but it is felt to be too polished and classical for a traditional Irish tune. The theory is that she must have had help improving it, and Ritter was the obvious local trained musician who could do it. The tune became known as The Londonderry Air, and later, Danny Boy .

An old tune as recorded in George Petrie’s The Ancient Music of Ireland – Volume 1 (1855), that later became known as The Londonderry Air. It is suggested Edward Ritter helped Jane Ross modernise the old tune she heard in the Derry mountains. Source: Journal of Music

There’s gold in them thar hills!

The Ritters’ time in Australia wasn’t uneventful either. In perfect timing, they arrived just before gold fever broke out in Australia in 1851 and he got rich buying gold from prospectors in Melbourne. In another sign that Jane’s father was the only one who didn’t like Ritter, her brother Samuel Maxwell Alexander set out to join Ritter in the gold rush.

In a notorious incident on 17 March 1853 Edward and Samuel were riding into Melbourne from their home in St Kilda when they stopped to water their horse and were set upon by seven or eight bushrangers. The assailants probably thought they would be carrying gold, as the banks had closed for St Patrick’s Day. When they found nothing, Edward presumed he was in for a severe beating, and bolted in his cart. The bushrangers fired at him with their pistols and hit him several times. Two bullets passed through his clothes, two grazed him, and one lodged by his shin, but he was not seriously injured. Samuel, sitting beside him, was unhurt. A reward was offered for £200 per head, and eventually several men were sentenced to 10 years for their role in the robbery.

Jane’s brothers all died without issue. Her brother Samuel, perhaps as a result of his gold exploits, added to their extensive landholding at Limavady by buying the Roe Park country house and estate (now a high-class golf resort). When he died, some of the inheritance likely passed to Jane, and so to her daughter Elizabeth Robertson, and the Robertson children.

Robertson children

The Robertsons had twelve children, four boys and eight girls. Andrew Robert and Edward stayed in Glasgow, the former, as noted, working for Watson Laidlaw & Co on centrifuges.

Edward founded The Robertson Engineering Company that developed the first turntable ferry, a classic of 20th century Scottish motoring . Once commonplace where water interrupted highland roads, there is now only one survivor, the MV Glenachulish to Skye.

The Glencoe at Ballachulish, the first turntable ferry, carries a rather unbalanced Robertson Engineering Co lorry, c 1912. Rather you than me. Source: Clyde River Steamer Club

Maxwell Robertson died at The Somme.

It is likely after RA’s death in 1900, his wife moved to her mother’s at Limavady, and the other children mostly lived and died in Limavady, either at Roe Park or nearby.

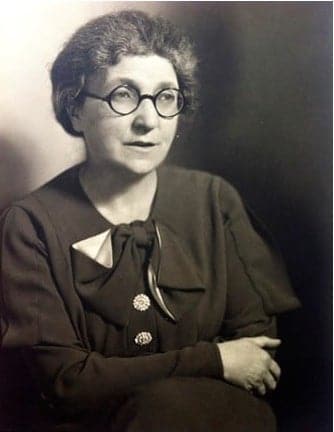

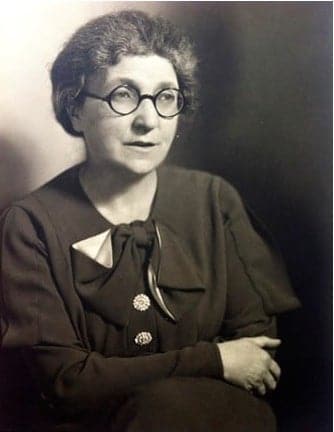

One notable exception was Muriel Robertson FRS, who studied at the University of Glasgow, then worked at the Lister Institute in London. She did important work on Clostridia, the cause of gas gangrene, and later on protozoa such as Trypanosomes. She travelled to Uganda during a major outbreak of sleeping sickness, and identified Trypanosoma brucei gambiense as the cause, and the Tsetse fly as the vector. She became one of the first female fellows of the Royal Society .

Muriel Robertson, FRS.

The Browns & Youngs

In 1876 Malcolm Brown, a wine and spirit merchant, moved from Albert Drive in Crosshill and took the house, but he died in November of that year. Thereafter his widow, Janet (nee Hay) continued the wine & spirit business at 97-99 Trongate for a couple of years before selling it on.

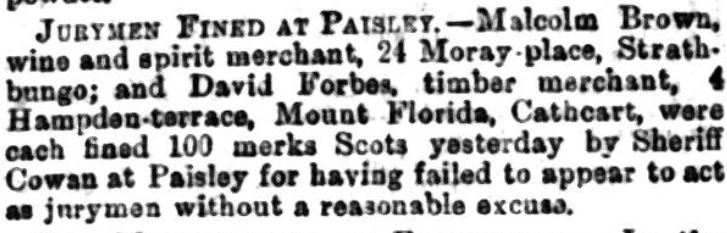

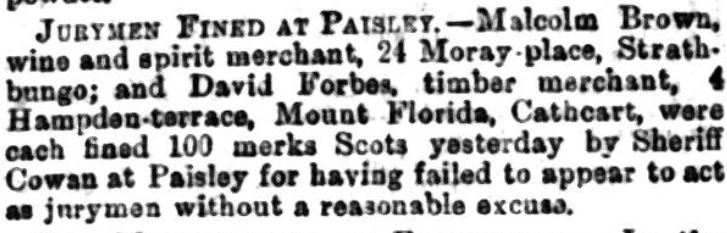

Confusingly in 1881 Malcolm Brown was fined 100 Scots merks for failing to turn up for jury duty without good excuse at Paisley Sheriff Court (at that time Strathbungo was still in Renfrewshire). Could being dead 5 years not be considered a good excuse? I can’t find any alternative explanation for this; there was another southside wine merchant at that time, Malcolm (Butler) Brown, but he appears neither to be related, not to have lived at Moray Place.

Surely Malcom Brown wasn’t fined for being long dead? I haven’t found an alternative explanation. Source: Glasgow Evening Citizen 21 June 1881, BNA

In 1881 Janet remarried, to a cashier & bookkeeper for a publishing firm, David Young, originally from Stirling. David had been living at Victoria Road, and then Matilda Terrace (Nithsdale Road) in Strathbungo, although they married in Edinburgh. David may have married wisely, as Janet, seven years his senior, was receiving the interest on Malcolm’s seemingly considerable estate. This would expire if she remarried, but she had already received almost £7000 in 1878. We know this from the account of a 1895 court case involving the estate, whereby the last annuitant, Malcolm’s father, died, and there were no offspring. His siblings claimed the residue, but the court ruled it should go to charity as per Malcolm’s wishes .

After 10 years or so, the couple rented out 24 Moray Place and moved to Crieff, where David described himself as retired, even though he was still in his 40s.

George Herriot

George Herriot rented the house in 1891, and subsequently bought it. The family would have the house for at least 50 years.

George was born in Blantyre in 1835, and married Isabella Scott in Rutherglen in 1859, moving shortly after to Liverpool as a sea-going engineer. They had 10 children. George gained experience running the Union blockades in the American Civil War. Blockade runners supplied the Confederates with arms and exported their cotton, and the City of Liverpool was a major supporter of the Confederates – indeed the civil war ended in Liverpool with the surrender of the CSS Shenandoah. Herriot was also involved in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, though his role is less clear.

He became an engineer for the White Star and Cunard Lines from Liverpool and for Norddeutscher Lloyd from Bremerhaven. Around 1876-8 he became a civil servant as a Board of Trade surveyor of steamships, and in 1892 became the principal engineer surveyor for the West of Scotland. His name crops up in newspapers at the initial trials of a number of ships, including The Fairy Queen on Loch Eck (1878), the SS Orient (second largest ship in the world at the time, on a run to Arran, 1879), Cunard’s Campania (1893) and the battleship Jupiter (1895) .

The steamer “Fairy Queen” of 1878 at the pier on Loch Eck.

In 1873 he was called as a witness as the former chief engineer on White Star Line’s SS Atlantic, regarding its rate of use of coal . This was of importance as a subsequent engineer had deliberately under-reported the remaining coal on a trans-atlantic voyage to encourage efficiency and save money. The ship fought storms en route, and as they approached the coast the Captain calculated they no longer had enough coal to reach New York. The engineer, John Foxley, knew this to be false, but couldn’t admit it without revealing his previous deceptions. So Capt Williams diverted to Halifax in Nova Scotia. The crew were unfamiliar with the port, the ship hit rocks and over 500 perished. It was White Star’s worst disaster, until The Titanic.

At the first enquiry White Star were upset to be severely criticised for providing too little coal. At a second enquiry they successfully argued that there was still plenty of coal on board at the time of the accident, and they didn’t deliberately undercoal their vessels. Herriot’s evidence helped exonerate them.

The Wreck of the Atlantic. Lithograph by Currier & Ives, 1873. Source: Wikipedia

He was a governor of Hutcheson’s Educational Trust, a JP, and chair, Royal Technical College and School of Art. He retired in 1900 and died at Moray Place in 1921 .

After his death three of his daughters lived on at Moray Place, Isabella, Elizabeth and Mary. Elizabeth died in 1933, Mary in 1941, and Isabella in 1959 at Glenafton Nursing Home in Pollokshields.

His son John Scott Herriot became a marine surveyor like his father, but in Belfast. John’s sons Thomas and George joined the Royal Naval Air Service in WW1, and George died when his seaplane crashed on a training flight. For some reason his grandfather’s Moray Place address is linked to him, such that he appears on the Glasgow Roll of Honour – his story is on the Strathbungo Roll of Honour post.

More recent occupants

in the 1950s & 60s the house was occupied by George Ewen Cameron Taylor, about whom I know nothing, except that he also bought 22 Moray Place in 1960 to split it into flats. In the 1990s there was Liz Brown, Secretary to The Strathbungo Society, and in the 2000s Paddy Higson, famed Scottish film producer. I distinctly recall her allowing the Taggart team to shoot scenes in her basement flat. Hopefully not a murder.

References

{3557955:B3PIEJRW},{3557955:EM25T8NA};{3557955:EM25T8NA};{3557955:B3PIEJRW},{3557955:HU8ATKMR};{3557955:BIMHP4DJ};{3557955:6YMXTTF6},{3557955:XPT8NW5L};{3557955:B3PIEJRW};{3557955:XBRSGLXI};{3557955:T4S4GVRK};{3557955:JIHRKV98};{3557955:3M2ZL4QU};{3557955:ZZ6SBVL4},{3557955:8T8N9WBG},{3557955:5ZDJ97AF},{3557955:SIEKKPQB};{3557955:RBY3BP47},{3557955:8FMDWTZB};{3557955:Z8FFCVNS},{3557955:VZ5KASD5}

vancouver

asc

0

4822

%7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3A%22zotpress-cc6cd4a3a4edb7ab7565e2ff570fab6b%22%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%223M2ZL4QU%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221898-06-08%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EHere%20and%20There.%20Perthshire%20Advertiser%20%5BInternet%5D.%201898%20Jun%208%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%2019%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000458%5C%2F18980608%5C%2F118%5C%2F0006%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000458%5C%2F18980608%5C%2F118%5C%2F0006%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Here%20and%20There%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2208%20June%201898%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000458%5C%2F18980608%5C%2F118%5C%2F0006%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T13%3A16%3A33Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22SIEKKPQB%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221895-11-19%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EThe%20Battleship%20Jupiter.%20Glasgow%20Herald%20%5BInternet%5D.%201895%20Nov%2019%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%2019%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2FBL%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18951119%5C%2F033%5C%2F0009%3Fbrowse%3DFalse%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2FBL%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18951119%5C%2F033%5C%2F0009%3Fbrowse%3DFalse%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Battleship%20Jupiter%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2219%20Nov%201895%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2FBL%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18951119%5C%2F033%5C%2F0009%3Fbrowse%3DFalse%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T13%3A15%3A33Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%225ZDJ97AF%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221893-04-17%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EThe%20New%20Cunarder%20Campania.%20Liverpool%20Mercury%20%5BInternet%5D.%201893%20Apr%2017%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%2019%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000081%5C%2F18930417%5C%2F023%5C%2F0006%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000081%5C%2F18930417%5C%2F023%5C%2F0006%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20New%20Cunarder%20Campania%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2217%20Apr%201893%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000081%5C%2F18930417%5C%2F023%5C%2F0006%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T12%3A51%3A38Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22ZZ6SBVL4%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221878-03-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EThe%20Loch%20Eck%20New%20Steamer%20Fairy%20Queen.%20Glasgow%20Herald%20%5BInternet%5D.%201878%20Mar%201%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%2019%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18780301%5C%2F019%5C%2F0006%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18780301%5C%2F019%5C%2F0006%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Loch%20Eck%20New%20Steamer%20Fairy%20Queen%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221%20Mar%201878%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18780301%5C%2F019%5C%2F0006%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T12%3A50%3A03Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22VZ5KASD5%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221921-07-21%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EDeath%20Of%20Board%20Of%20Trade%20Ex-Official.%20Dundee%20Evening%20Telegraph%20%5BInternet%5D.%201921%20Jul%2021%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%2019%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000563%5C%2F19210721%5C%2F093%5C%2F0007%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000563%5C%2F19210721%5C%2F093%5C%2F0007%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Death%20Of%20Board%20Of%20Trade%20Ex-Official%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2221%20Jul%201921%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000563%5C%2F19210721%5C%2F093%5C%2F0007%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T12%3A38%3A22Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22Z8FFCVNS%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221900-04-26%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ERetiral%20of%20Mr%20George%20Herriot.%20Glasgow%20Herald%20%5BInternet%5D.%201900%20Apr%2026%20%5Bcited%202024%20Jul%2016%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F19000426%5C%2F023%5C%2F0006%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F19000426%5C%2F023%5C%2F0006%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Retiral%20of%20Mr%20George%20Herriot%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2226%20Apr%201900%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F19000426%5C%2F023%5C%2F0006%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T12%3A29%3A18Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%228FMDWTZB%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%222024-06-04%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ESS%20%3Ci%3EAtlantic%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%281870%29.%20In%3A%20Wikipedia%20%5BInternet%5D.%202024%20%5Bcited%202024%20Jul%2016%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fen.wikipedia.org%5C%2Fw%5C%2Findex.php%3Ftitle%3DSS_Atlantic_%281870%29%26oldid%3D1227226889%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fen.wikipedia.org%5C%2Fw%5C%2Findex.php%3Ftitle%3DSS_Atlantic_%281870%29%26oldid%3D1227226889%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22encyclopediaArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22SS%20%3Ci%3EAtlantic%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%20%281870%29%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22encyclopediaTitle%22%3A%22Wikipedia%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222024-06-04T14%3A32%3A21Z%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fen.wikipedia.org%5C%2Fw%5C%2Findex.php%3Ftitle%3DSS_Atlantic_%281870%29%26oldid%3D1227226889%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T12%3A23%3A09Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%228T8N9WBG%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221879-09-10%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ETrial%20Trip%20Of%20The%20S.S.%20Orient.%20Glasgow%20Herald%20%5BInternet%5D.%201879%20Sep%2010%20%5Bcited%202024%20Jul%2016%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18790910%5C%2F023%5C%2F0004%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18790910%5C%2F023%5C%2F0004%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Trial%20Trip%20Of%20The%20S.S.%20Orient.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2210%20Sep%201879%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0000060%5C%2F18790910%5C%2F023%5C%2F0004%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T12%3A22%3A54Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22RBY3BP47%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%221873-05-31%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EThe%20Loss%20of%20the%20Atlantic.%20Liverpool%20Journal%20of%20Commerce%20%5BInternet%5D.%201873%20May%2031%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%2019%5D%3B%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0004034%5C%2F18730531%5C%2F065%5C%2F0005%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0004034%5C%2F18730531%5C%2F065%5C%2F0005%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22newspaperArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Loss%20of%20the%20Atlantic%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2231%20May%201873%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk%5C%2Fviewer%5C%2Fbl%5C%2F0004034%5C%2F18730531%5C%2F065%5C%2F0005%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-19T12%3A20%3A45Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22BIMHP4DJ%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Caird%20and%20et%20al%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221901%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ECaird%20R%2C%20et%20al.%20Local%20Industries%20of%20Glasgow%20and%20the%20West%20of%20Scotland%20%5BInternet%5D.%20British%20Association%20for%20the%20Advancement%20of%20Science%3B%201901%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%208%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.scottishcorpus.ac.uk%5C%2Fcmsw%5C%2Fdocument%5C%2F%3Fdocumentid%3D44%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.scottishcorpus.ac.uk%5C%2Fcmsw%5C%2Fdocument%5C%2F%3Fdocumentid%3D44%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Local%20Industries%20of%20Glasgow%20and%20the%20West%20of%20Scotland%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Caird%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22et%20al%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221901%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.scottishcorpus.ac.uk%5C%2Fcmsw%5C%2Fdocument%5C%2F%3Fdocumentid%3D44%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-11T08%3A29%3A23Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22JIHRKV98%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22parsedDate%22%3A%222024-05-19%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EMuriel%20Robertson.%20In%3A%20Wikipedia%20%5BInternet%5D.%202024%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%206%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fen.wikipedia.org%5C%2Fw%5C%2Findex.php%3Ftitle%3DMuriel_Robertson%26oldid%3D1224649456%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fen.wikipedia.org%5C%2Fw%5C%2Findex.php%3Ftitle%3DMuriel_Robertson%26oldid%3D1224649456%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22encyclopediaArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Muriel%20Robertson%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Muriel%20Robertson%20%2C%20FRSTM%2C%20F.I.Biol%20%288%20April%201883%20%5Cu2013%2014%20June%201973%29%20was%20a%20Scottish%20protozoologist%20and%20bacteriologist%20at%20the%20Lister%20Institute%2C%20London%20from%201915%20to%201961.%20She%20made%20key%20discoveries%20of%20the%20life%20cycle%20of%20trypanosomes.%20She%20was%20one%20of%20the%20founding%20members%20of%20the%20Society%20for%20Microbiology%20%2C%20along%20with%20Alexander%20Fleming%20and%20Marjory%20Stephenson.%22%2C%22encyclopediaTitle%22%3A%22Wikipedia%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222024-05-19T16%3A41%3A34Z%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fen.wikipedia.org%5C%2Fw%5C%2Findex.php%3Ftitle%3DMuriel_Robertson%26oldid%3D1224649456%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-06T16%3A10%3A03Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22T4S4GVRK%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EThe%20crossing%20at%20Ballachulish%2C%20Scotland%20-%20PreWarCar%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%206%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.prewarcar.com%5C%2Fthe-crossing-at-ballachulish-scotland%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.prewarcar.com%5C%2Fthe-crossing-at-ballachulish-scotland%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20crossing%20at%20Ballachulish%2C%20Scotland%20-%20PreWarCar%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Before%20the%20construction%20of%20the%20Ballachulish%20Bridge%20%28that%20now%20carries%20the%20A82%2C%20the%20main%20route%20between%20Glasgow%20and%20Inverness%29%20in%20the%20West%20Highlands%20of%5Cu00a0Scotland%2C%20the%20only%20way%20to%20cross%20the%20narrows%20between%20Lock%20Leven%20and%20Loch%20Linnhe%20was%20by%20ferry.%5Cn%5CnThe%20video%20shows%20ME%201699%20crossing%20from%20North%20Ballachulish%20to%20South%20Ballachulish%2C%20reportedly%20in%201926.%20In%20the%20distance%20we%20see%20the%20Ballachulish%20Hotel%20on%20the%20Argyll%5Cu00a0side.%5Cn%5CnIn%20later%20years%20the%20standard%20of%20the%20boat%20was%20improved%20as%20the%20vehicle%20traffic%20on%20the%20ferry%20increased.%20By%20the%201960s%20the%20crossing%20was%20operated%20by%20three%5Cu00a0turntable%20roll-on%2C%20roll-off%20ferries%2C%20each%20capable%20of%20carrying%20six%5Cu00a0cars.%20However%2C%20this%20all%20came%20to%20an%20end%5Cu00a0in%201975%20with%20the%20opening%20of%20the%20Ballachulish%20Bridge.%5Cn%5CnCan%20anyone%20tell%20us%20more%20about%20ME%201699%5Cu00a0seen%20in%20the%20video%3F%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.prewarcar.com%5C%2Fthe-crossing-at-ballachulish-scotland%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-06T15%3A59%3A53Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22XPT8NW5L%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EBibliotheca%20Augustana%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%206%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.hs-augsburg.de%5C%2F~harsch%5C%2Fgermanica%5C%2FChronologie%5C%2F20Jh%5C%2FDiesel%5C%2Fdie_edpr.html%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.hs-augsburg.de%5C%2F~harsch%5C%2Fgermanica%5C%2FChronologie%5C%2F20Jh%5C%2FDiesel%5C%2Fdie_edpr.html%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Bibliotheca%20Augustana%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.hs-augsburg.de%5C%2F~harsch%5C%2Fgermanica%5C%2FChronologie%5C%2F20Jh%5C%2FDiesel%5C%2Fdie_edpr.html%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-06T11%3A57%3A07Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22HU8ATKMR%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Guariento%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222021-06-09%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EGuariento%20K.%20Sugar%20Machines%3A%20How%20Archives%20in%20Glasgow%20hold%20pieces%20of%20Caribbean%20History%20%5BInternet%5D.%20University%20of%20Glasgow%20Library%20Blog.%202021%20%5Bcited%202024%20Jul%2018%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Funiversityofglasgowlibrary.wordpress.com%5C%2F2021%5C%2F06%5C%2F09%5C%2Fsugar-machines-how-archives-in-glasgow-hold-pieces-of-caribbean-history%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Funiversityofglasgowlibrary.wordpress.com%5C%2F2021%5C%2F06%5C%2F09%5C%2Fsugar-machines-how-archives-in-glasgow-hold-pieces-of-caribbean-history%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22blogPost%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Sugar%20Machines%3A%20How%20Archives%20in%20Glasgow%20hold%20pieces%20of%20Caribbean%20History%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Kate%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Guariento%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Guest%20blog%20post%20by%20Dr%20Christine%20Whyte%2C%20Lecturer%20in%20Global%20History%2C%20University%20of%20Glasgow%20On%2020%20May%2C%20in%20response%20to%20the%20%23MuseumsUnlocked%20discussion%2C%20Twitter%20user%20%40j4lebi%20asked%3A%20It%20strikes%20me%20that%20co%5Cu2026%22%2C%22blogTitle%22%3A%22University%20of%20Glasgow%20Library%20Blog%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222021-06-09T11%3A55%3A18%2B00%3A00%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Funiversityofglasgowlibrary.wordpress.com%5C%2F2021%5C%2F06%5C%2F09%5C%2Fsugar-machines-how-archives-in-glasgow-hold-pieces-of-caribbean-history%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-06T10%3A26%3A41Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%226YMXTTF6%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EAnson%20Engine%20Museum%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%206%5D.%20A%20brief%20history%20of%20Mirrlees%20Blackstone.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fenginemuseum.org%5C%2Fabout%5C%2Fhistory-mirrlees-blackstone%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fenginemuseum.org%5C%2Fabout%5C%2Fhistory-mirrlees-blackstone%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20brief%20history%20of%20Mirrlees%20Blackstone%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Find%20out%20more%20about%20the%20Mirrlees%20Blackstone%20engine%20company%2C%20and%20key%20events%20in%20its%20history.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fenginemuseum.org%5C%2Fabout%5C%2Fhistory-mirrlees-blackstone%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en-GB%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-06T10%3A15%3A11Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22EM25T8NA%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Trust%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ETrust.%20Thames%20Festival%20Trust.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Jul%2017%5D.%20Thames%20Festival%20Trust%20-%20The%20Islanders%3A%20Tate%20%26amp%3B%20Lyle.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fthamesfestivaltrust.org%5C%2Fheritage-programme%5C%2Fthe-islanders%5C%2Fthe-islanders-4-tate-lyle%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fthamesfestivaltrust.org%5C%2Fheritage-programme%5C%2Fthe-islanders%5C%2Fthe-islanders-4-tate-lyle%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Thames%20Festival%20Trust%20-%20The%20Islanders%3A%20Tate%20%26%20Lyle%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Trust%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20industrial%20and%20community%20heritage%20of%20Silvertown%20%26%20North%20Woolwich.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fthamesfestivaltrust.org%5C%2Fheritage-programme%5C%2Fthe-islanders%5C%2Fthe-islanders-4-tate-lyle%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-05T15%3A32%3A51Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22XBRSGLXI%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3EThe%20Journal%20of%20Music%20%7C%20News%2C%20Reviews%20and%20Opinion%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%205%5D.%20A%20Long%20Drive%20from%20Limavady.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjournalofmusic.com%5C%2Ffocus%5C%2Flong-drive-limavady%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjournalofmusic.com%5C%2Ffocus%5C%2Flong-drive-limavady%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20Long%20Drive%20from%20Limavady%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20melody%20of%20%5Cu2018Danny%20Boy%5Cu2019%20has%20its%20origins%20in%20the%20middle%20of%20the%20nineteenth%20century%20in%20the%20North%20of%20Ireland.%20An%20old%20harper%5Cu2019s%20melody%20was%20collected%20and%20embellished%20to%20make%20the%20air%20that%20we%20know%20today%2C%20but%20by%20who%3F%20Brendan%20Drummond%20explores%20some%20of%20the%20contemporary%20theories%20and%20uncovers%20a%20new%20European%20twist%20to%20the%20tale.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjournalofmusic.com%5C%2Ffocus%5C%2Flong-drive-limavady%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-05T14%3A52%3A38Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22B3PIEJRW%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A3557955%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%201.35%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22clear%3A%20left%3B%20%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-left-margin%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22float%3A%20left%3B%20padding-right%3A%200.5em%3B%20text-align%3A%20right%3B%20width%3A%201em%3B%5C%22%3E1.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-right-inline%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22margin%3A%200%20.4em%200%201.5em%3B%5C%22%3ERobert%20Andrew%20Robertson%20-%20Graces%20Guide%20%5BInternet%5D.%20%5Bcited%202024%20Aug%205%5D.%20Available%20from%3A%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.gracesguide.co.uk%5C%2FRobert_Andrew_Robertson%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.gracesguide.co.uk%5C%2FRobert_Andrew_Robertson%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%20%20%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Robert%20Andrew%20Robertson%20-%20Graces%20Guide%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.gracesguide.co.uk%5C%2FRobert_Andrew_Robertson%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22CAR6MXPM%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222024-08-05T14%3A42%3A14Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D

Like this:

Like Loading...

September 24, 2024 at 9:56 pm

I have no way of knowing this but I cant help feeling that we are duller than previous residents of Strathbungo. I dare say I am only qualified to speak for myself but honestly, what a history for just one house. Quite remarkable.