11-17 Moray Place was the second terrace constructed along Moray Place, and said to be a poorer imitation of Greek Thomson’s style for the first, though its architect is unknown. It was completed soon after the first terrace however, within a year of 1-10.

No 13 was taken by William Stevenson, the 35 year old quarrymaster of Baird & Stevenson. It was Stevenson, with John McIntyre the builder, who had purchased the land of Strathbungo from Sir John Maxwell and began the development of the area.

The house remained in the Stevenson family for the next 60 years, and this article largely concerns the dynasty built by William Stevenson and his sons.

Many are aware of the two-tone nature of Glasgow’s buildings – blond sandstone in the 19th century, increasingly replaced by red sandstone in the 20th, allowing buildings to be roughly dated before or after the 1890s. However few are aware that, blond or red, the odds were the stone was supplied by the Stevensons. No one person can claim to have made a greater mark on Victorian Glasgow’s architecture and appearance than William Stevenson; Glasgow University, the City Chambers, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and countless others were built from Baird & Stevenson stone. Yet apart from a brief contemporary obituary in the Barrhead Times, virtually nothing has been written about William Stevenson, and he seems completely forgotten. So here is his story.

You can read for yourself the database entry for 13 Moray Place on which the article is based.

William Stevenson

William was born on 17 April 1827 at Mid Hareshaw Farm, on Clunch Road near Stewarton, to Hugh Stevenson and Elizabeth Craig. While a child the family moved to Newton Mearns, but his father died before he was 12, and so William had to leave school. He sought employment with William Hill, who managed a number of toll roads around Glasgow. He took charge of the Eglinton Toll Bar, and the associated licensed premises, and made many contacts there (the Toll was rebuilt in the 1870s and now houses The Star Bar). One of the most important sources of income on the toll roads was carters bringing in building stone from quarries outside the city, and one acquaintance, a quarrier at Giffnock, was so impressed by Stevenson he offered him the job of clerk at his quarry. When the owner retired, Stevenson and the quarry foreman took on the business as Baird & Stevenson , probably in 1854. The oldest mention of the firm is in a newspaper article in 1855 .

Baird & Stevenson, Quarymasters

William married Jane Brownlie of Pollokshaws in 1852 and started a family. He became a member of the Incorporation of Masons of Glasgow on 22 April 1857, when he had just turned 30, and he became their Deacon in 1862 . In 1858 he first appeared in the Glasgow Post Office Directory, as Baird & Stevenson, stone merchants, of 259 Eglinton Street, managing the Orchard and Giffnock quarries.

His new partner, presumably the former quarry foreman referred to above, was De Hort Baird. Baird was born in England c.1798 to William Baird, a freestone quarrier, and Margaret Smith. He became a quarryman in Pollokshaws, marrying Margaret Gray from Neilston in 1818. He had four daughters and one son, William, who also became a quarry manager, possibly for Baird & Stevenson. William’s son in turn, another De Hort, emigrated to the USA and ran quarries there. De Hort the elder was a councillor for Pollokshaws from 1856 to 1865, serving as Baillie in 1857, the year he also chaired a ball for 150 Baird & Stevenson managers and employees at Pollokshaws . He died aged 71 at High Cartcraigs, Pollokshaws in 1869, two years after his wife.

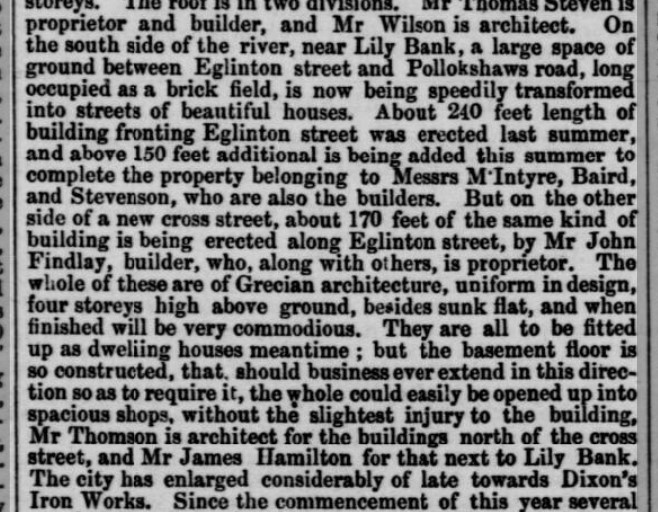

A newspaper article from May 1858 reports on building activity in Glasgow, and describes plans to finish a long tenement on Eglinton Street, the first half of which had been completed the previous year. The land had previously been occupied by a brickfield (run by a David Baird in the 1830s, but no relation), but the development was by McIntyre, Baird and Stevenson, with the architect Thomson .

This was an important partnership; John McIntyre being the builder, De Hort Baird and William Stevenson supplying the stone from Giffnock, and Alexander “Greek” Thomson as the architect. The building they were constructing was later considered Thomson’s finest tenement, Queens Park Terrace (1856-60). Tragically. Glasgow Council tore it down in 1980, despite it being A-listed . Baird & Stevenson’s first address, 259 Eglinton Street, was in the already completed half of Queens Park Terrace, and he and his family were living above the premises.

The birth of Strathbungo

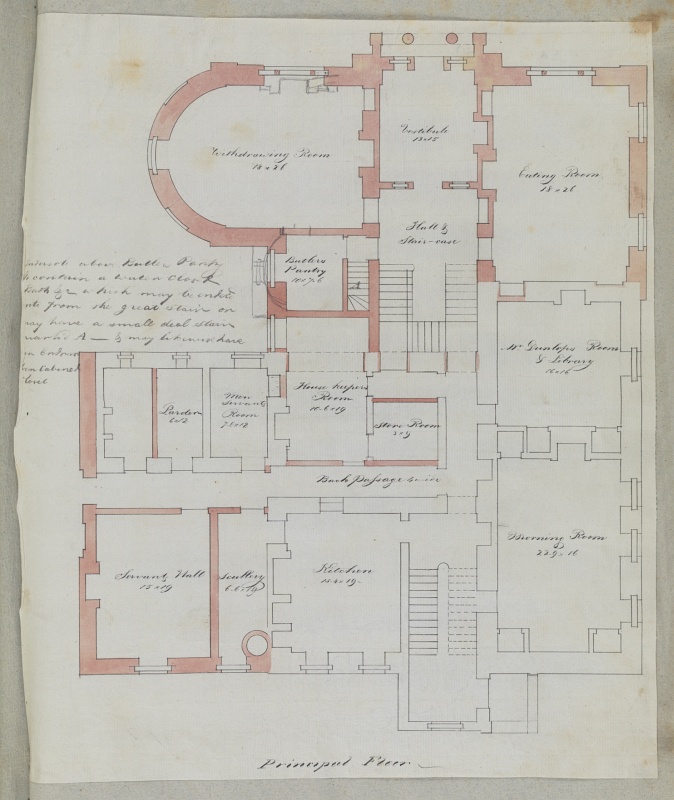

The following year McIntyre and Stevenson negotiated the purchase of land from Sir John Maxwell that led to the development of Strathbungo, and set about laying out the street grid we now know. They built 1-10 Moray Place to the design of Alexander “Greek” Thomson. They probably built 11-17 Moray Place to a different design, given it was built within a year, and Stevenson chose to live in this terrace. However they then sold on the other plots to other developers. The 1861 census recorded Stevenson as employing 10 men & 4 boys in his quarries, the year before he moved from Eglinton Street into his new house in Strathbungo.

William fairly quickly bought out his partner Mr Baird, and took sole control of the company , and in the following years his career really took off. By the 1871 census he was at 13 Moray Place with his wife Jane and their five children, Jane Brownlie (likely Jane’s mother), Jessie Wilson, a visitor, and two servants. He then employed 501 men and 239 boys, quite a change in 10 years. Business was aided by the opening of the Busby Railway in 1866, which linked Giffnock to South Side Station in the Gorbals via a junction with the Glasgow, Barrhead and Neilston Direct Railway at Busby Junction. A mineral railway ran from Giffnock Station into the Orchard and Braidbar quarries. Baird & Stevenson also had a depot at the Gushetfaulds Coal Terminal beside South Side Station (and across the road from Thomson’s new Caledonia Road Church), and so stone from Giffnock could easily be moved to the city by rail and, as it happens, passing by William’s front window on Moray Place en route.

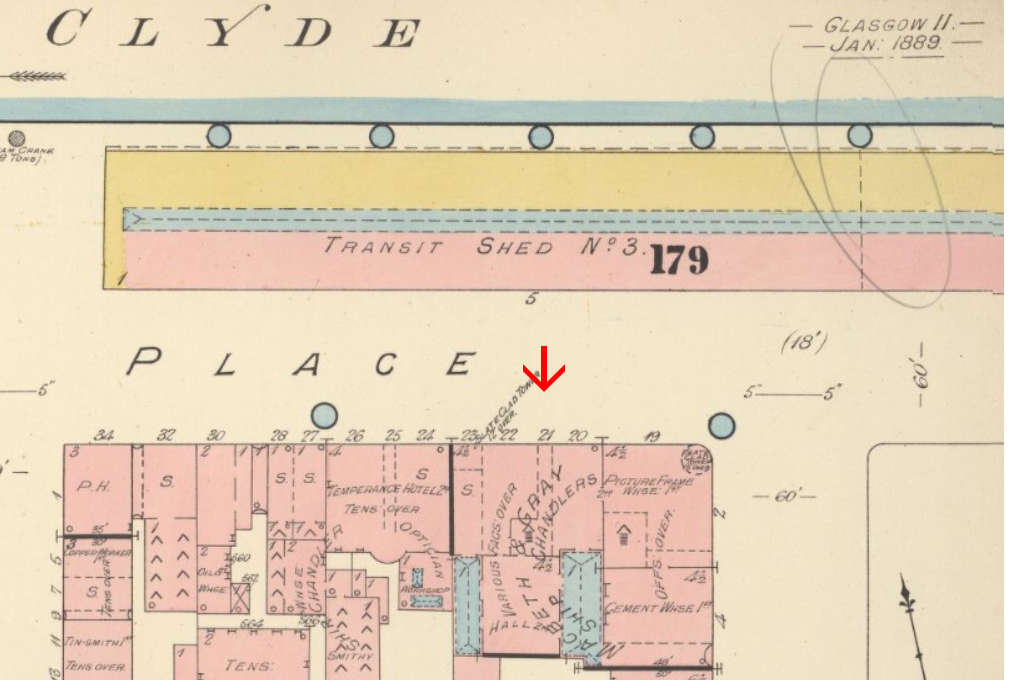

Baird & Stevenson had offices at 20 Dixon Street (1871), and later 21 Clyde Place, on the river opposite the Broomielaw (now part of the new Barclays development). They also used 13 Carlton Place in the 1890s.

Hous’hill

In 1872 Jane died. About that time William purchased Hous’hill estate for £40,000. This was a property in Hurlet, Nitshill with a house revised in the early 19th century by David Hamilton, the noted architect who designed The Royal Exchange in Glasgow, and possibly Camphill House in Queens Park. At the time the property was noted to contain, in addition to the mansion house, a village, an ironwork, clay-fields, a brick work, coal and ironstone mines and quarries, which might explain his interest.

William marries again

In 1874 he married again, this time to Annie McCreath, 26, and twenty years his junior. Annie was from a family of civil and mining engineers. Annie’s father William and subsequently her elder brother James were the managers of John Wilson & Sons’ coal, limestone, and alum-shale pits at Nitshill, close to William’s new home. I am told of a family story which recalls how a pretty young girl had caught William’s eye at a family wedding. There may be some grain of truth in this; William’s marriage to Annie took place only a few weeks after William’s eldest daughter Jane had married Annie’s older brother George!

In 1881 the family were at Househill, except Jane and George McCreath who had moved back to Strathbungo, at 10 Princes Square (now known as 22 Marywood Square), and Hugh the eldest son, who had stayed on at 13 Moray Place with his young family. As well as a quarrymaster, employing 580 men and 20 boys, William was also a farmer, employing 10 men on his 280 acre estate.

Hawkhead

In 1886 William spotted another opportunity. The Earl of Glasgow had invested heavily in the Episcopal Church, such as a college and church, later The Cathedral of the Isles, on Cumbrae. In 1886 his loans were called in, and he was forced to dispose of most of his extensive lands and houses in Renfrewshire and Ayrshire. One such was the Hawkhead Estate near Paisley, and William continued his ascendancy by purchasing the estate house and three farms to the south for £200,000 over Christmas 1886. This formed a tract of land continuous with his land at Househill to the south-east. The plot to the north east of Hawkhead was sold separately by the Earl, and used for the Govan District Asylum, later Leverndale Hospital, designed incidentally by Strathbungo architect Fred Rowntree and his partner Malcolm Stark.

In 1891 William was still at Househill but by 1901 he was living in the mansion at Hawkhead, with his wife Annie, his son James, 44, by his previous marriage, and their three now adult sons George, John and Thomas. They had four servants.

All his sons became involved in the quarries in some way. The four sons from his first marriage, Hugh, James, William and Alexander had already followed him into the business – they all became members of the Incorporation of Stonemasons of Glasgow on 24 April 1878, just after Alexander turned 18. The three younger boys from his second marriage, George, John & Thomas, did likewise, and were admitted to the Incorporation on 4 November 1896. From the 1880s onwards he maintained overall control, but increasingly left the running of the quarries and the business to his sons, and took more of an interest in public life.

From 1882 to 1893 he was a councillor for Govan Ward, serving on many Town Council committees, in 1886 a depute river baillie, and from 1887 a burgh magistrate. William was also a fan of sports, and kept race horses; his horse Bosphorus came a disappointing fourth in the 1891 St Leger Stakes as his jockey had taken ill, while his horses won the Lanark Silver Bell trophy three times.

The fate of Househill and Hawkhead

In the mid 1890s he let Househill to Andrew Mitchell JP, a Dundee & Glasgow linen merchant. In 1904 he leased Househill House to John Cochrane, the Provost of Barrhead, and his wife Kate Cranston, famous for the Willow Tea Rooms and her association with Charles Rennie & Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh. On moving in Kate commissioned the Mackintoshes to redecorate the house. When they left the furniture was sold to the next tenant, Arthur Gamble, and when the Stevenson estate sold the house to Glasgow solicitor John Henderson in 1927 for £2900, Gamble auctioned the furniture separately. The house was severely damaged by a fire in 1934, during a heatwave while the Hendersons sat in the garden, and the house was later demolished. Glasgow Corporation acquired the estate for a park and housing estate .

Mackintosh chair for Kate Cranston at Househill. Now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Richmond, VA.

William died at Hawkhead in 1910, and in 1914 the estate was annexed to the adjacent Govan District Asylum, which was renamed Hawkhead Asylum, and then Hawkhead Mental Hospital. The land to the west of the house was used for the Paisley Infectious Diseases Hospital in 1936, designed in the art deco style by Thomas Tait (who later built Tait’s Tower in Bellahouston Park for the Empire Exhibition). Hawkhead House was demolished in the 1950s. When Hawkhead Asylum changed its name again to Leverndale in 1964, the Paisley hospital adopted the name Hawkhead Hospital. The estate’s West Lodge and several of the Hawkhead Hospital buildings survive in the new Hawkhead Village housing development.

Hawkhead’s West Lodge, with the art deco Hawkhead Village behind, from Hawkhead Road. Credit: Google Streetview

NLS geo-referenced maps show the location of Househill and Hawkhead Estate.

Dominance in the stone business

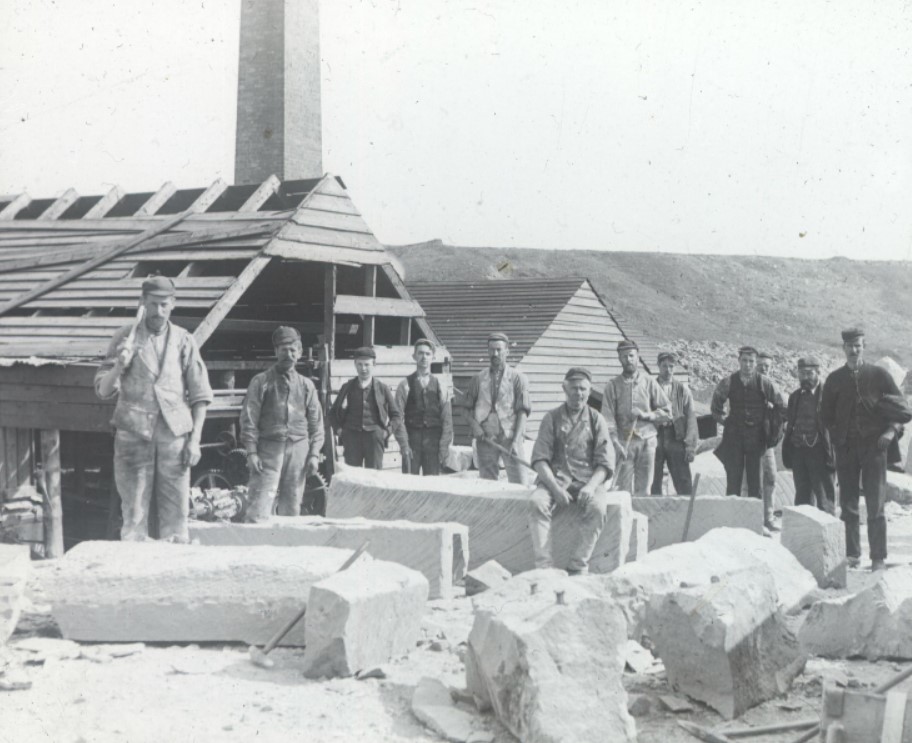

The business became massively successful, to the point where much of late Victorian Glasgow was built with stone quarried by the Stevensons, and his obituary stated “he became widely known as one of the largest and most successful quarry masters in Scotland” . An 1894 trade directory summarises the company thus:

THIS firm of quarry masters control probably the largest business of the kind in Scotland, and have been established, with headquarters in Glasgow, for upwards of forty years. During that period they have developed the trade, and have built up a large connection. The various classes of building and other stone supplied by them has an unsurpassed reputation for durability and appearance. Messrs. Baird & Stevenson’s quarries are situated in different parts of Scotland. The white freestone is quarried at Giffnock (south of Glasgow), Dunmore (near Bannockburn), Overwood (Stonehouse), Colston, Bishopbriggs, and Grange Quarry, Burntisland, Fifeshire. The firm have also freestone quarries at Monkreddon, Kilwinning. The redstone quarries are at Locharbriggs (Dumfries), and Montgomerie and Barskimming (Mauchline, Ayrshire); and the blue-grey stone comes from their quarry at Linlithgow. Messrs. Baird and Stevenson employ many hundreds of hands at their various quarries. For years they have supplied most of the builders and contractors in and around Glasgow with building stone, &c.; and among the many notable buildings that have been constructed with their stone may be mentioned the following:- Glasgow University, St. Enoch Station and Hotel, the Glasgow General Post Office, the Glasgow Municipal Buildings, the George A. Clark Halls at Paisley, the Gartloch Asylum, the Central Agency Buildings, the Roman Catholic College at Bearsden, the Dumfries General Post Office, the Barracks at Dumfries, &c., &c. Modern Glasgow may be said to have been chiefly built with stone supplied by this firm, and in many other parts of Scotland there are fine buildings which testify to the vast resources of Messrs. Baird and Stevenson’s quarries. The whole business is ably directed from the head offices in Clyde Place, Glasgow, and is under the control of Mr. William Stevenson, senior, and his sons, who are in partnership with their father.

Quarries with which he appears to have been associated include Orchard, Giffnock, Overwood, Dunmore, Nitshill, Netherton, Monkredding, Chapelhall, Ravenscraig, and Jamestown.

Glasgow’s Stone

The article gives a hint to the Stevensons’ importance to late Victorian Glasgow. In the early history of the city, up to mid 19th century, stone for buildings was difficult to move any distance, and was extracted locally. There were many small quarries in the city. For instance the Tron Church (1807) in Nelson Mandela Place was probably built of stone quarried at the top of Buchanan Street, and Queen Street Station was built within an old quarry . As the city expanded these were abandoned and quarriers needed to look further out. Initially stone was moved by horse and cart over poor roads, but as the railways developed moving this stone became easier and much of Glasgow’s famous blond sandstone came either from the quarries of Giffnock or those at Bishopbriggs. The article above suggests Baird & Stevenson acquired Bishopbriggs too, although I can find no other evidence of Baird & Stevenson’s involvement in Bishopbriggs. As the blond sandstone began to run out, red sandstone from further afield became commonplace in the 1890s; the Stevensons cornered that market too, acquiring the Barskimming quarry, one of two in Mauchline, Ayrshire, and opening the Locharbriggs quarry outside Dumfries. The latter was the main source of red sandstone in Glasgow and is the only building stone quarry still operating in Scotland today. Thus it is easy to see why the Stevensons might be responsible for the stone of most late Victorian Glasgow buildings. The finest example of this is expressed in the company’s advert for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901 – the Palace of Fine Arts (now Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum) is built with their Locharbriggs red sandstone on the outside, but lined with their Giffnock blond on the inside.

The Giffnock Quarries

The first Giffnock quarry is thought to have opened around 1835-40. Many websites, including Wikipedia, reference the Renfrewshire Council site “Portal to the Past” (temporarily unavailable as at 2022) which claimed the Giffnock Quarries were taken over in 1854 by two famous civil engineers, Hugh Baird and Robert Stevenson (the latter of “Rocket” fame), but this turns out to be fanciful.

There were multiple quarries at Giffnock and it isn’t certain the Stevensons operated all of them, but their quarries became renowned and a bit of a tourist attraction, with accounts appearing in local papers.

Description of a geological excursion to Giffnock. North British Daily Mail, 14 May 1874. Credit: BNA

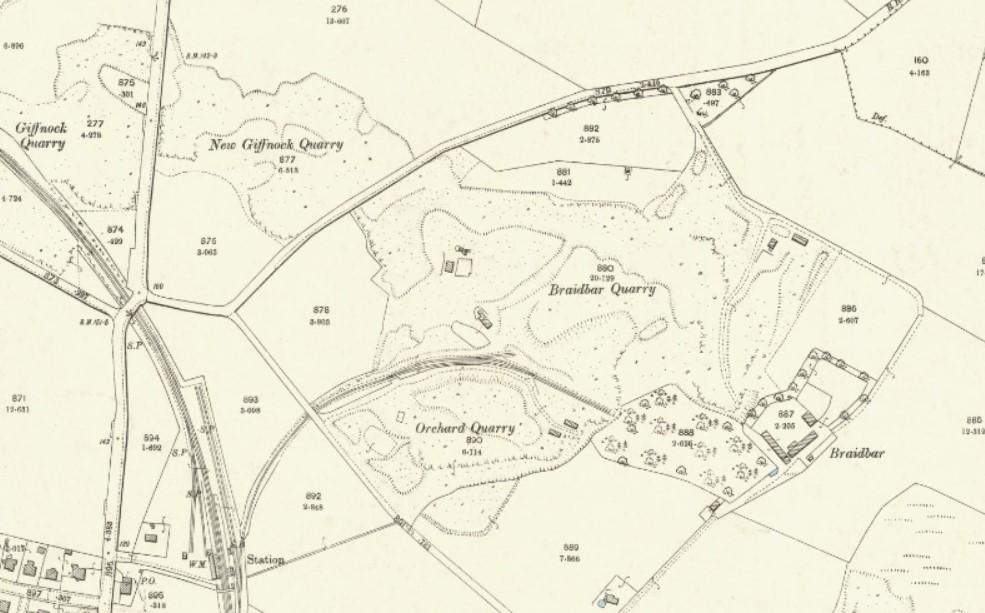

OS Map 1895. Giffnock Station,

with branch to Orchard & Braidbar Quarries (now Braidpark Drive). Credit: NLS

The Giffnock quarries were abandoned around 1912, and later used for dumping slag from the Beardmore Park Forge steelworks until the 1960s. The more dangerous parts remain fenced off to this day in Huntly Park.

Barskimming Quarry

This was the later of the two main quarries in Mauchline, Ayrshire. The lease for the quarry was taken on ground at the rear of Mosshead Farm by Baird & Stevenson and quarrying began around 1890. The quarry was connected to the Glasgow and South Western Railway by a narrow gauge rope-worked incline which hauled bogie wagons up to a railway siding just north of Barskimming Road Railway Bridge. Here the stone was transferred to railway wagons and the spoil dumped just opposite Mauchline Cemetery. Traces of the incline are still visible today. This was probably the largest of all the quarries believed to cover an area of 5 acres. The quarry had ceased producing stone by the beginning of the First World War. A newspaper article from November 1916 has the company dismantling plant, boilers, machinery and rail track to be used elsewhere .

Dunmore

Stone from Dunmore in Stirlingshire was used for many central Glasgow buildings, such as the City Chambers .

Overwood

Stone from the quarry near Stonehouse was used for the Stock Exchange Building in Glasgow .

Locharbriggs Quarry

Locharbriggs was the most important source of red sandstone for Glasgow buildings and extensively used once the blond sandstone became less available, and rail transport was available from Dumfries. The stone was also used further afield, such as the Caledonian Hotel in Edinburgh. Widely repeated claims it was used for the steps of the Statue of Liberty and for New York brownstone terraced houses are less easy to prove.

Other quarries managed by Baird & Stevenson at some time include Scares Quarry in Old Cumnock, Garscube Quarry in Maryhill, Nitshill Quarry in Hurlet, Netherton, Chapelhall, Ravenscraig, Jamestown, and Newcastleton.

McCreaths & Stevenson, Jane Stevenson

William McCreath was the mine manager at Nitshill, whose daughter became William Stevenson’s second wife, and whose son George Wilson McCreath married William’s daughter Jane. The McCreaths became well established civil and mining engineers, eventually forming the firm of McCreaths & Stevenson. Son James McCreath, born at Nitshill, was particularly active around the turn of the century, providing reports and surveys of Scottish mines, and became a sought after opinion, and an inspector of mines. He died in 1910, although the firm was still active as recently as 1941 . He lived at Levern House, Bothwell, with two of his sisters and brother John, all apparently unmarried. George McCreath, his younger brother, was born in Old Monkland (Coatbridge) and also became a civil engineer working for the firm. He and Jane had four children, who they brought up in Strathbungo, first at 10, then at 41 Princes Square (now 23 Marywood Square), where he died in 1927. Jane died there in 1932.

Marywood Square

The Stevensons had an odd link to the south side of Princes (now Marywood) Square. This long terrace was built several years after the other sandstone terraces of Strathbungo, probably due to the financial crisis that followed the 1878 collapse of the City of Glasgow Bank, just as the north side was completed. The south side was built c.1884-5 and in the 1885 valuation roll the entire terrace was listed as belonging to James Robertson, a mason and builder living in Pollokshields. He first advertised the houses for sale or let in the spring/summer of 1884. Yet in the early 1890s he went bankrupt, and by 1895 the valuation roll notes the entire terrace was then owned by William Stevenson.

William still owned the unused land in Strathbungo, and would have sold the land to Robertson for development, or perhaps had a hand in it himself. He may have spotted an opportunity to buy it back cheaply when Robertson’s business was sequestrated. If anyone in that terrace has a copy of their deeds I would love to take a look to clarify this! Some of his children took up residence in the terrace (including Jane McCreath, as noted above), but most were rented, and on his death each child inherited two or three of the houses.

Hugh Stevenson

William left 13 Moray Place in 1872, though still the owner; his son Hugh, now 26, and managing a quarry himself, was living there with his wife Margaret and new daughter. Hugh raised his family there and eventually inherited the house. He also inherited 49 & 50 Princes Square (5 & 3 Marywood Square). He spent almost his entire life in the one house; he was still resident when he died in 1921, as was his wife when she died while visiting Bournemouth in 1923.

His wife Margaret Glover was the daughter of Robert Glover, a woollen merchant who lived at 23 (now 5) Regent Park Square.

James Stevenson

James, William’s second son, was a commercial clerk in 1881, but became a quarrymaster like his brothers, and was living with his father at Househill and at Hawkhead. He inherited 47 & 48 Princes Square (9 & 7 Marywood Square), and then lived at no 47 (9 Marywood Square). He married Marion Bowman but she possibly died after childbirth in 1889. Their daughter May Bowman Stevenson married John Campbell Murray, an engineer who had grown up in Haggs Castle; his father, also John Campbell Murray, was the factor to Sir John Stirling Maxwell of the Pollok estate. James died at 9 Princes Square in 1925, and his daughter and son-in-law lived there initially after his death.

William Stevenson

William, third son, was born in Pollokshaws in 1858. Another quarry master, he married Mary Jane Glover, the younger sister of Margaret, who had married his brother Hugh. He inherited 38, 39 and 40 Princes Square (25, 27 & 29 Marywood Square) in 1910, and lived at 40 with his family, probably from around 1895 onwards, next door to his sister Jane McCreath. He died in 1919 and his wife remained in the property.

Alexander Stevenson

Alexander was born on Eglinton Street in 1860. He was a commercial clerk in 1881, but later a quarrymaster. He inherited 31, 32 and 33 Princes Square (43, 41 and 39 Marywood Square) but around 1913 onwards he was living at Collinswell, Burntisland, Fife. He was likely the manager of the firm’s Grange Quarry there, which produced high quality sandstone for Edinburgh. He married Jane Turner and had a daughter Agnes. He later lived at Closeburn Castle in Dumfries, and died there in 1945. 41 Marywood Square later passed to a Mrs E T or E Y Stevenson, 1925-1939, though I have not been able to identify her.

George Stevenson

George was the first child of Annie McCreath, born 1876. He became a mechanical engineer. He didn’t appear to inherit any properties in Marywood Square, but I don’t know why, as I have no further information about his life; the last record is of him living at Hawkhead in 1901.

John Stevenson

Born in 1878, he received his first mate’s certificate in 1899, and was recorded as a shipping clerk in the 1901 census. He was residing at Dunlop at time of his father’s death in 1910, and inherited 34, 35 & 36 Princes Square (37, 35, 33 Marywood Square). He was known as Sugar Johnnie (Edith Anne Ward, Ancestry). He died in South Africa in 1936.

Thomas Stevenson

Thomas became a stockbroker and also took an interest in horses. He was living in Princes Square at the time of his father’s death and inherited 43, 44 & 46 Princes Square (19, 17 and 11 Marywood Square). He later lived at Amisfield, Mansewood Road, and died in 1957.

James Aitken

James Aitken was a writer (solicitor) at 92 St Vincent Street in Glasgow who appears to have been involved in the Stevensons’ affairs. By 1900 he was living at 45 Princes Square (15 Marywood Square) and in 1905 according to the valuation roll he was already the owner of this and most of the other properties described here. I presume William had passed ownership of most of them to a trust in favour of his children, and James was the trustee. After 1910, when Wiliam died, ownership passed to the children listed here, apart from No 45 which James got to keep for himself.

Margaret Stevenson

She inherited 28 & 30 Princes Square (45 & 49 Marywood Square) in 1910. She was living at 1 Albert Gate, Dowanhill in 1913. According to a relative, she was “a very annoying twittery little woman”. She was first engaged to the brother of James Laird – her sister Bessie’s husband – however after breaking the engagement off several times when things did not go her way, she found the young man did not return on the last occasion. Her marriage to James Hayes was quite short lived and her brother Thomas looked after her financially, including paying for a taxi which she insisted on taking to visit friends – a journey from Glasgow to Newcastle!

Elizabeth Stevenson

Elizabeth married James Laird and had a daughter Dorothy. She inherited 25, 26 & 27 Princes Square (now 55, 53 and 51 Marywood Square) from her father. She died in 1945. Her daughter’s obituary (in 2000) described Elizabeth as a disabled painter.

The fate of Baird & Stevenson

The company was eventually absorbed into the Tarmac Group, who still operate the Locharbriggs quarry near Dumfries. The name was revived as a Tarmac brand from time to time, most recently disappearing in November 2019.

The Provands

In 1925 the valuation roll records Mary Provand as the owner occupier of 13 Moray Place, and in 1939 the Post Office Directory records the Rev W S Provand as the occupant.

William Seath Provand was born on 16 November 1855 in Glasgow to William Tarbet Provand and Helen Seath. He qualified with an MA from Glasgow University in 1880, and became minister of St Ninians Church on Albert Drive & Pollokshaws Road from 1897 until 1924. The church had opened in 1877, named after St Ninian’s Leper Hospital which existed in the Gorbals up to 1730 – also the origin of Hospital Street.

He married Mary Davison and had two sons, the first named Dixon after his brother, and the second Ninian after his church and parish. The family moved to 18 Moray Place (now 53 Queen Square) around 1915, and then to 13 Moray Place sometime between 1920 and 1925. Dixon died in France in the Great War on 15 Sep 1916 and is mentioned in the Strathbungo Roll of Honour. Ninian served in the Royal Naval Reserve and became an electrical engineer in civilian life.

William died in 1943 and his wife in 1957.

Additions and corrections are welcome.

March 23, 2022 at 10:55 am

Fascinating – great work, Andrew.

June 5, 2022 at 1:22 pm

Did you come across any mention of stone being supplied for gravestones and associated memorials?