Biographies of most of the major players in the building of Strathbungo including land owners, builders and architects.

- Charles Wilson

- Sir John Maxwell

- Alexander “Greek” Thomson

- John McIntyre

- William Stevenson

- Robert Turnbull

- Daniel McNicol

- William Brown

- James Watson

- Francis Armstrong

- Robert Weir

- Alexander Thomson

- James Robertson

- Andrew McIntyre

- William Howie

- John Bennie Wilson

- John McKissack

- James Wright

- Gardner & Glen

- William Todd Aitkenhead

Charles Wilson

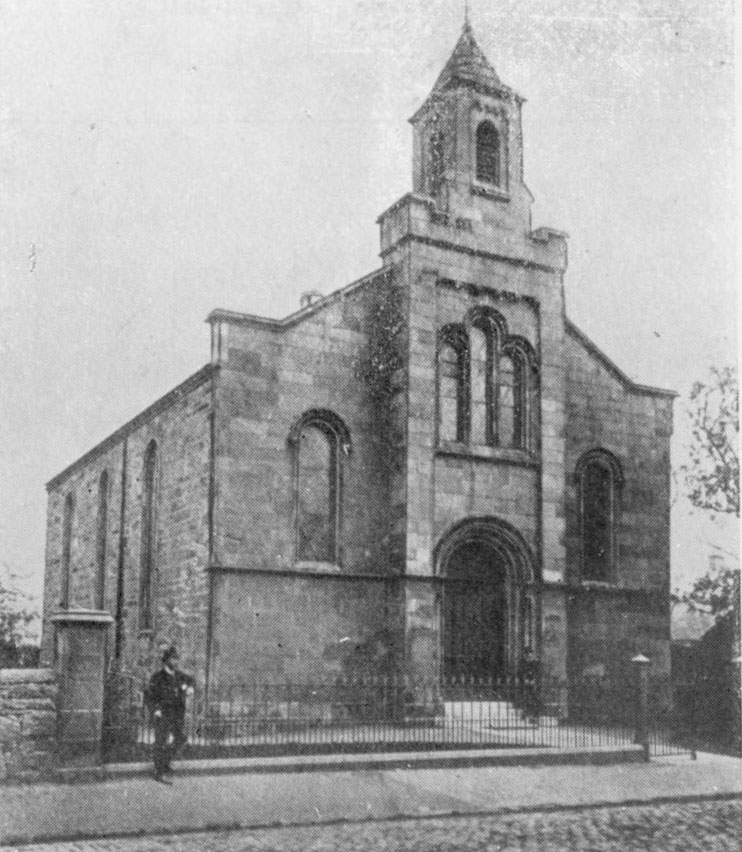

Charles Wilson was the architect of the first Strathbungo Parish Church. This biography is an excerpt from the Proceedings of the Philosophical Society of Glasgow, 1908 – Some Notable Scottish Architects, by Alexander Gardner .

Charles Wilson was the son of a builder in Glasgow, and was born there in 1810. At the age of 17 he became a pupil of David Hamilton, and was for some time Hamilton’s chief assistant. While in this position, Wilson had the good fortune to be engaged on Hamilton Palace, Lennox Castle, Toward Castle, the Royal Exchange, Campsie Parish Church, St PauFs Church, the Normal School, and other large, though less noted, works. In 1837 he began business, and in that year designed Hutchesontown Church, Hospital Street. In 1839 the church at Strathbungo was built from Wilson’s designs, and about the same time a church of Greek design in Calderwood Street, Parliamentary Road. A list of his executed works is a somewhat lengthy one, and includes many important buildings in the city, among them being the Royal Lunatic Asylum at Gartnavel; Windsor Terrace, Great Western Road; the Glasgow Academy, now the High School, in Elmbank Street, one of his best designs; Shandon House, Gareloch; the Gateway at the Southern Necropolis; Free St Peter’s and St Stephen’s Churches; Royal Bank Buildings, Buchanan Street; Faculty of Procurators’ Hall in George Place, perhaps his finest work; laid out Kelvingrove Park in conjunction with Sir Joseph Paxton; Park Terrace, Gardens, and Circus, with the fine granite stairs there; Free Church College and College Church in Lynedoch Street; the Queen’s Rooms and La Belle Place adjoining; Thornliebank House; Lewis Castle at Stornoway; Raasay Castle, Island of Raasay; Rutherglen Free Church and the Town Hall there; Free Churches at Rothesay, Melrose, &c.; at Oban the Great Western Hotel, and at Paisley the Neilson Institution, besides a great number of other churches, mansions and town properties. A very able paper on Wilson’s works was read to this Section 25 years ago by Mr David Thomson, a former President of this Section. The paper is printed in the Proceedings of the Philosophical Society Vol. XIII , to which I would refer those who wish to make a fuller acquaintance with Charles Wilson and his works. Wilson died at Glasgow in 1863, at the comparatively early age of 53.

Old Strathbungo Parish Church, 1839 by Charles Wilson

Sir John Maxwell

Sir John Maxwell, 8th Baronet of Pollok (1791-1865) was the major southside landowner who lived at Pollok House, and who feued Strathbungo with John McIntyre & William Stevenson in 1859-60.

He married Matilda Bruce, daughter of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, he who took the Elgin Marbles from Greece. Matilda Place and Terrace were presumably posthumously named for her; she passed away in 1857. The tenement on Pollokshaws Road where The New Regent sits was originally named Elgin Place.

Alexander “Greek” Thomson

Thomson was one of Glasgow’s most famous architects, who designed 1-10 Moray Place, and lived at No 1 for the rest of his life. The following biography is taken from the Dictionary of Scottish Architects .

Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson was born at Endrick Cottage, Balfron, on 9 April 1817, the seventeenth child of John Thomson and the ninth child of his second marriage to Elizabeth Cooper. John Thomson was the bookkeeper at Kirkman Finlay’s cotton works there and had previously held a similar position at Carron Ironworks. Advancement with both firms was precluded by his strict Burgher beliefs which were shared by his wife: she had come to Balfron with her brother, the Rev John Cooper. The family was educated at home, partly by Cooper, but John Thomson died in 1824 and the family had to move from Balfron to the outskirts of Glasgow. Elizabeth died in 1828, leaving the family in the care of her son William, a brilliant classical scholar who was briefly professor of humanity at the University of Glasgow.

In 1834 William Thomson moved to London as a missionary, leaving his brothers and sisters at his house at Hangingshaw. In the same year Alexander became a clerk in a Glasgow lawyer’s office. There his drawing skills attracted the attention of a client, Robert Foote, who had inherited the large plasterer’s business of David Foote & Son in 1827 and had commenced practice as an architect in 1830. Foote’s architectural practice was small but in association with the decorative plasterwork side of his business he had amassed a magnificent library and a large collection of classical casts from which Thomson learned much in the two years he was articled to him. In 1836 a spinal complaint obliged Foote to withdraw from architectural practice and Thomson completed his articles with John Baird, remaining with him first as assistant and later as chief draughtsman when much of his time was spent on the unbuilt college on Woodlands Hill. In the early 1840s Thomson’s younger brother George, born at Balfron on 26 May 1819 was also articled to Baird, after recovering from a respiratory complaint which had been thought to be consumption.

On 21 September 1847 Alexander Thomson married Jane Nicholson, daughter of the London architect Michaelangelo Nicholson and granddaughter of the architect-writer Peter Nicholson. It was a double wedding, her sister Jessie marrying another John Baird (‘Secundus’) who, although an architect, had no family or professional connection with the Thomsons’ employer. Born in Ayr in November 1816, Baird was some five months older than Thomson. He had been articled first to James Watt and then to John Herbertson before finding a place in the office of David and James Hamilton where he was, very unusually, named in the Directory entry. After David Hamilton died in 1843 and his firm was sequestrated in 1844, Hamilton’s son-in-law James Smith continued his practice and John Baird commenced practice on his own account. After the financial problems of the Hamilton and Smith businesses were resolved Smith and Baird merged their practices as Smith & Baird. Their partnership does not seem to have been a happy one and was dissolved in 1848 when Baird invited his brother-in-law to join him, the new partnership being entitled Baird & Thomson.

Within two years the Baird & Thomson partnership was extremely successful with a large clientele for medium-sized villas and terraces of cottages in Pollokshields, Shawlands, Crossmyloof, Cathcart, Langbank, Bothwell and Cove and Kilcreggan. At Cove and Kilcreggan they enjoyed the support of the builder, railway contractor and ironfounder John McElroy who commissioned Craig Ailey in 1850 and built a considerable number of other marine villas either speculatively or for clients. These early villas were generally either Gothic, sometimes with Pugin-derived details, or Italian Romanesque but a few, most notably Glen Eden at Cove, had very original elements which, as Gavin Stamp has shown, have their origins in the publications of the architectural historian and theorist James Fergusson.

In 1854 Thomson began designing in a picturesque, asymmetrically-composed, pilastraded, neo-Greek idiom which derived from Schinkel at Rockbank, Helensburgh and the Mossman studio on Cathedral Street. These were followed by the Scottish Exhibition Rooms in Bath Street which he and some architect friends built to provide a Scottish counterpart to the period courts in the Crystal Palace at Sydenham. This decisive shift to the neo-Greek which would remain characteristic of him and by then had no counterpart either in Edinburgh or south of the Border was quickly followed by a change of partner. In 1856 the partnership of Baird & Thomson was amicably dissolved so that Thomson could form a separate practice with his brother George who may still have been in the office of John Baird Primus: the record is not absolutely clear. The new partnership quickly acquired influential contacts, notably the builder John McIntyre. Others were probably made through UP Church contacts.

In 1856-57 Thomson’s architecture developed rapidly. The neo-Greek of Rockland achieved a much more sophisticated maturity in the Double Villa at Langside and his finest house, Holmwood at Cathcart. In the same years a more monumental but still asymmetrical Greek idiom was applied to church design at Caledonia Road UP, where both the lower façade and the tower were of Schinkelesque banded masonry. This banded treatment was extended into the adjoining tenement blocks for which he devised a repetitive bay design with pilastered first-floor aedicules and third-floor recesses containing anthemeon ornament. In the following year, 1857, this theme was further developed on a vast scale at Queens Park Terrace in which Thomson adopted his familiar device of linked Egyptian architraves set against a recessed wall plane and omitted the banded masonry. With subtle variations this formula was to remain a feature of his more upmarket tenements for the remainder of his career. The same motifs, now with a top-floor pilastrade, were to feature at Walmer Terrace and the first of his commercial blocks, 99-107 West Nile Street, both built in 1857.

In 1858 Alexander and George Thomson bought the Gordon Street UP Church in which they worshipped in order to build a showpiece warehouse with ground-floor shops – a fairly innovative concept at the time – in which the David Hamilton theme of interpenetrating pilastrades was developed into the same repetition of absolutely regular single-bay units, here much more complex in design, crowned by a deeply shadowed eaves gallery. It did indeed attract commissions for similar structures in which the same themes were further developed with an ever-increasing subtlety in which overlaid and superimposed pilastrades and dwarf eaves gallery colonnades varied the original formula. The Gordon Street development financed the Gordon Street congregation’s new church in St Vincent Street, built in 1857-59, which again must have been intended as an advertisement for their services. Stylistically it marked a further advance drawing upon wider areas of antiquity than Caledonia Road, but in the event it attracted only one further church commission, that for Queen’s Park Church, built in a similar but externally less ambitious idiom in 1868-69.

Thomson’s widely recognised professional successes in the 1850s were clouded by a series of tragic events at home. In the early years of their marriage Alexander and Jane lived at 3 South Apsley Place in Laurieston. Agnes Elizabeth was born on 24 April 1849, Elizabeth Cooper on 31 January 1851 and Alexander John on 27 November 1852. But Laurieston, although then still a good address, proved vulnerable to the cholera epidemic of 1854 and on 14 March of that year Agnes Elizabeth died. Jane Nicholson, born 8 August 1854, died on 13 February 1855, George born 8 August 1855 survived only until 31 December 1856, and on 3 January 1857 Alexander John died leaving Elizabeth Cooper the only survivor from a family of five. Later in that year the Thomson household moved to Darnley Terrace, a recently completed development he had designed at Shawlands. There on 12 April Amelia was born, followed by Jessie Williamina on 10 April 1858 and the future architect son John on 20 June 1859. In 1861 the Thomsons moved again to Moray Place in Strathbungo, taking the northmost house in a two-storey terrace block built as a speculative venture in association with his measurer John Shields and the builder John McIntyre. Designed in 1859 it was predictably the finest and most original of his earlier terraces, the large end houses being advanced and pedimented with a giant order of pilasters. There Helen was born on 9 July 1861, Catherine Honeyman on 11 February 1863, and Michael Nicholson on 13 October 1864. Peter was born on 19 March 1866, but survived only sixteen days. The size of Alexander Thomson’s family seems to have restricted travel. Family holidays were invariably spent in a rented house on Arran. His only recorded trip to London was in 1861 when he visited John James Stevenson, but he may well have made earlier visits. His knowledge of antiquity and of contemporary architecture seems to have been derived from a magnificent library and from the building journals, one of these being the ‘British Architect’, of which he was one of the founding shareholders in 1874.

In the 1860s the practice was notably prosperous, in large part as a result of the developments undertaken by the accountant Henry Leck, the cab hirer John Ewing Walker and the builder William Henderson who was the client at North Park Terrace (1863-66); 126-138 Sauchiehall Street (1864-66); 249-259 St Vincent Street (1865-67); Grecian Buildings, 252-270 Sauchiehall Street (1868-69); and Great Western Terrace (begun 1869). All of these were built with borrowed money and the practice must have suffered a notable drop in income when Henderson died in May 1870, his property being sequestrated in June. With the practice at a relatively low ebb George Thomson carried out his long-planned intention of becoming a missionary and emigrated to the Cameroons in the Spring of 1871, although he was to remain a partner until 1873.

By 1872 Thomson was in failing health because of asthma and bronchitis, and it was probably because of illness that in February of that year Henry Leck, hitherto a faithful client, commissioned first John Baird and then Peddie & Kinnear to design his building on Gordon Street, replacing an earlier Thomson scheme for a different site which had been stalled by the Caledonian Railway’s proposals for Glasgow Central Station. In February 1874 Thomson took Robert Turnbull into a partnership which was backdated to October 1873, probably on account of services rendered since that date. Born in 1839, Turnbull was the son of William Turnbull, joiner and his wife Mary Deans and was more inspector of works than architect, engaged for the ‘outdoor’ side of the business as correspondence with the Thomson trustees in July 1876 makes clear. But through the family joinery business he did bring new clients in the Lenzie area, for which earlier Thomson villa designs were either reused or adapted. The immediate catalyst for this partnership may have been Thomson’s commitment to the Haldane lectures, a series of four delivered in the Spring of 1874. These were a final statement of ideas developed in earlier lectures delivered from 1853 onwards, most of them to the Glasgow Architectural Society and the Glasgow Institute of Architects. These he had co-founded in 1858 and 1868 respectively: he was President of both, the Society in 1861 and the Institute from 1870 to 1872.

In August 1874 Thomson wrote to his brother that ‘Mr Turnbull and I are getting on pretty well we are busy with a number of smallish jobs’. But in the winter of 1874-75 his asthma and bronchitis deteriorated and his decision to winter in Italy to regain his health had been left too late. Thereafter he worked mainly at Moray Place and at the time of his death on 22 March 1875 he had been working on a competition design for a town hall. This may have been for Paisley or for Annan, or more probably both: the Annan design is preserved in a relatively coarse presentation perspective made after his death.

In 1897 one of Alexander Thomson’s former assistants, William Clunas, put on paper a vivid pen portrait of him at the request of Thomas Ross, together with an indication of what it was like to work in his office. Clunas remembered him as:

a distinguished looking man of good average height, stout, well and proportionally made, a fine manly countenance with a profuse head of hair. His general appearance was indeed, very much in harmony with the strength and elegance which he imparted to the structures he designed, while the genial smile which so often overspread his face might be fittingly compared to the finished enrichment which was so marked and pleasing a feature of his compositions.

In general character he was very unassuming and to those in his employment he was always considerate and even affectionate. By his professional brethren he was held in the highest esteem if one judged from the numbers of the best of them who used to call upon him.

His pupils were well aware of the great Art Master they were under and experienced the inconveniences as well as the advantages of such a position … for the strictly professional side of business he had little capacity – punctual he was not, neither was he persevering. You could not say he was indolent, but there was a dreamy unrest about him even when engaged on important work which caused matter-of-fact people who were waiting for further details or instructions some annoyance. But when he did plunge in to a piece of work his attitude was that of a real devotee – patient, forceful, and painstaking … While in the mood for work he was apparently urged on by the idea that was moving him … at one time buried in thought, at another wielding the pencil with vigour and precision … His habit in designing was to sketch the work on a small scale on a scrap of paper, and in the course of his cogitations scores of these scraps of paper would be lying rejected about the floor, each with a miniature design that never failed to display the master hand, but to the master himself it was an oft-repeated effort before he was satisfied.

A notable feature of Mr Thomson’s character was his social friendliness. This he displayed in no way more strikingly than the frequent occasions when he had his pupils at his house. He delighted to speak of examples of antiquity of past ages as well as the more familiar antiquarian lore of his own country. Even ghost and fairies’ stories were not beneath his notice.

There is no record of when Clunas was in the office, but the absence of any reference to George suggests that it was in 1871-73. But it can be read as indicating the importance of George’s role as the business manager of the practice and explain why the practice briefly went into relative decline until Turnbull took over its management in the autumn of 1873. Turnbull took a more commercial attitude to style, recycling or adapting Gothic and Romanesque designs of the 1850s if they better met the wishes of his clients. Of Thomson himself Campbell Douglas recalled in 1889:

In my experience I have only known one man who confined himself to one style, and if his proposed employers insisted on building in a different style, why, then, he let them go elsewhere. That architect was a great man, who probably made less money than some others did, but he left behind him monuments more worthy of his genius.

Thomson’s moveable estate, none of which was inherited, was in fact one of the largest left by any nineteenth-century Glasgow architect at £15,395 5s 6d; he also had substantial property interests.

Alexander was buried in the Southern Necropolis. George came back from the Cameroons to help settle his affairs and marry Isabella Johnston, who returned with him to the Cameroons to help run the missionary hospital he had designed and built in 1874. He died of a fever at Victoria on 14 December 1878.

Note on Alexander’s son, John:

In 1889, on 11 April, Thomson’s son John married Annie M Muir, daughter of James Muir, pattern designer and ward of the Shields family who lived two doors from the Thomson’s at 3 Moray Place. John Shields was Alexander Thomson’s measurer.

John McIntyre

John McIntyre was the builder who worked with William Stevenson and Alexander Thomson in developing 1-10 Moray Place. He occupied number 2 Moray Place (not no 3 as often stated elsewhere). He subsequently moved to 40 (now 41) Regent Park Square, in 1868, and then over the railway line in Lorne Terrace, another Thomson designed building, in 1871.

He also operated the Glasgow Brick and Tile Works on Lilybank Road, off Eglinton Street, possibly in partnership with Alexander Thomson (the brickmaker, not Greek Thomson the architect) , under the name McIntyre & Thomson. This partnership appeared to be active again in 1871, Thomson living at 259 Eglinton Street.

McIntyre died in 1872, to be buried under the tomb Thomson had designed in 1867 for McIntyre’s son, in Cathcart Old Parish churchyard. The brick and tile business was wound up and the equipment sold in 1875 after his death .

For more on the McIntyres, see also 2 Moray Place.

William Stevenson

Following further research, there is now a full and fascinating biography of William Stevenson and his family.

William Stevenson was a partner in the business of Baird & Stevenson, Quarrymasters, of 21 Clyde Place. He partnered the builder John McIntyre in the deal to buy the land for the building of modern Strathbungo. His quarries in Giffnock were the source of the blond sandstone with which the terraces of Strathbungo were built.

Sandstone was first quarried in Giffnock in 1835. The principal workings for Giffnock sandstone lay either side of the present Fenwick Road; Braidbar, New Braidbar, Orchard, Williamwood, Giffnock, New Giffnock, English and Flag Quarries.

The quarries produced two types of rock known as “liver rock” and “moor rock”. Liver rock was very popular with quarrymen, masons and sculptors due to its lack of stratification, making it easy to work. Moor rock was harder, more porous and less valued as building stone.

In 1854 the Glasgow coal-mining firm of Baird and Stevenson took over the quarrying operations at Giffnock and in 1864 the Glasgow-East Kilbride railway was built, thus enabling the transport of stone by rail. The quarries were worked by excavating the liver rock, forming walls and pillars, while the moor rock above formed roofs. This has been referred to as the “stoop and room” method. Some older residents of Giffnock have memories of playing as children in the cavernous tunnels of the disused quarries.

Quarry workers worked on average for ten hours a day, six days a week and earned two shillings a day. The main customer for the stone was, not surprisingly, Glasgow and Giffnock itself. Well-known buildings made of Giffnock sandstone included the older part of Glasgow University; the eastern side of the former Post Office in George Square; Glasgow Savings Bank (now the TSB) in Ingram Street; the Scottish Co-op Building in Morrison Street; and the interior of Kelvingrove Art Gallery. Alexander “Greek” Thomson also used the sandstone in some of his villas, for example “Holmwood” in Netherlee, and presumably in 1-10 Moray Place.

Quarrying in Giffnock continued until 1912 when, due to flooding and the increasingly high cost of extracting the stone, work ceased .

Meanwhile the company owned other quarries in the West of Scotland, including Barskimming Quarry in Mauchline , and the Overwood Quarry near Storehouse, the source of stone for the Stock Exchange in Nelson Mandela Place. They also owned Locharbriggs Quarry in Dumfriesshire. As the blond sandstone began to run out, the railways permitted the use of stone from further afield, and Locharbriggs was the main sources of the red sandstone that began to replace it. Buildings in Glasgow can be roughly dated from their colour; blond older than 1900, red later than 1890. There is probably no better example of this than the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1901 International Exhibition (better known now as Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum), built from Baird & Stevenson Locharbriggs red sandstone on the outside, and their Giffnock blond sandstone on the inside.

Catalogue of the International Exhibition 1901

Baird & Stevenson have been absorbed into Tarmac, but Locharbriggs Quarry still operates to this day.

Stevenson was the Deacon of the Incorporation of Masons of Glasgow for the year 1862.

He purchased the Hawkhead Estate in 1886 , although by 1895 the site had become Govan District Asylum, and later Leverndale Hospital . The house was demolished in the 1950s. Much of the estate has now been developed into housing.

Robert Turnbull

Born in Mossburnford, he trained with his father, William Turnbull, from the age of eleven, then studied at the Watt Institute, Edinburgh, and at Anderson’s College, Glasgow (now University of Strathclyde) .

In 1873, he became a partner of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson; looking after the business side of the practice and supervising construction, a role which enabled Thomson to concentrate exclusively on design.

After Thomson’s death in 1875, with David Thomson (no relation) as his new partner, 1876-83, they completed the old firm’s outstanding contracts and adapted Thomson ‘s unexecuted designs for new clients.

The city’s southern suburbs are particularly rich in their post- Thomson work, and includes several tenements and villas in Pollokshaws and Pollokshields, e.g., the convex, Graeco-Egyptian, Salisbury Quadrant, Nithsdale Drive (c. 1878), and the serenely elegant, 2-38 and 40-46 Millbrae Crescent (1876-7).

The West End and other prosperous districts also received their quota of Thomsonesque tenements and houses.

However, lacking the subtlety of Thomson ‘s original ideas, much of their work has become almost indistinguishable from that of the city’s other Thomson imitators, e.g., Alexander Skirving.

Turnbull’s son, Robert, became a partner after David Thomsons’s departure in 1883, and the firm continued into the 20th Century.

Turnbull was buried at the Auld Aisle Cemetery, Kirkintilloch, his grave marked by a Thomsonesque monument which he designed for his first wife in 1877.

Daniel McNicol

McNicol was the builder of Regent Park Square and the north side of Queen Square, c.1864-5.

His biography comes from a chance internet encounter with a great great grand daughter, Lesley Bathgate, who had posted his will on line. This included reference to all his tenants in 1872, listed as living at 1 Regent Park Square and 2 Queen Square, but which in fact matched the residents of the entire length of Regent Park Square and Queen Square at the time.

Born 29 January 1825 in Bonhill, the son of Archibald McNicol, an agricultural labourer, and Margaret McKenzie, he was the eldest of their five known children. He was christened Donald, but appears to have been known as Daniel.

In 1841 the family were living at Ruchetmoss, when he was a mason apprentice at the age of 16, but by 1851 he was lodging in Pollock St, Pollokshaws. He married Susan Davie, daughter of James Davie & Susannah Guy on 2nd December 1852, and lived in the Anderston area of Glasgow at Dumbarton Road, then Elderslie Street, but in the 1860s he moved to Elgin Villas on Pollokshaws Road, Shawlands (8 (or 9?) Elgin Villas is probably now 1401 Pollokshaws Road, or thereabouts). His wife died on 27 February 1867 of tuberculosis.

By 1871 he was a master mason, living with his sister as housekeeper, his five children, and employing 12 men, 2 boys and 3 labourers. He died 9 November 1872 aged 47, of pneumonia. A very brief death notice appeared in the Glasgow Herald on 11 November, and he was buried in the Southern Necropolis.

Note that William Hair, house factor, who is mentioned as the person to whom funeral accounts were to be sent following Daniel’s death, had a business at 79 Robertson Street, where James McNicol later had his House Factor’s business. The older business was known as Hair & Stevenson and William Stevenson, Quarry Master, residing at Regents Park & William Hair House Factor in Glasgow and James Davie, Shoemaker in Partick (brother of Daniel’s wife, Susan Davie) were all trustees mentioned in Daniel’s will. As trustees they had control of the estate until 1885 when the youngest surviving son, Alexander, reached 21 years (although Stevenson had declined to be a trustee following the death of Daniel). At this time the houses were sold to the benefit of Daniel’s surviving sons, James, Daniel and Alexander, all of 492 Paisley Road, Glasgow; the estate amounted to £3161-8-6d, to be split 3 ways, the sons receiving £1058-16-2d each.

It is interesting that McNicol retained ownership of all the properties, acting as landlord, rather than selling them following their completion.

William Brown

After many years trying, I have finally identified William Brown, who built 18-25 Moray Place c 1872-4. He was born in Carstairs in 1825 to James Brown and Marion Wallace. In 1850 he married Margaret Scott in Lanark, and settled in Glasgow where he worked as a mason. By 1861 he was a master mason employing 38 men and two boys, and was living near Eglinton Toll with a growing family; in total they had five children.

He was the first developer to buy from McInyre & Stevenson, building two tenements on Pollokshaws Road from Nithsdale Road to Queen Square in 1862. He then built the third tenement in 1867. These were then known as Regent Park Terrace, though now they only go by their street numbers. The fourth tenement was by a different contractor.

The family moved into one of his apartments, living at 6 Regent Park Terrace (now 794 Pollokshaws Road). In 1872 he commenced work on the third Moray Place terrace, but he died of bronchitis at only 49 the following year, as the building was being completed. Neither of his two sons followed him in the business.

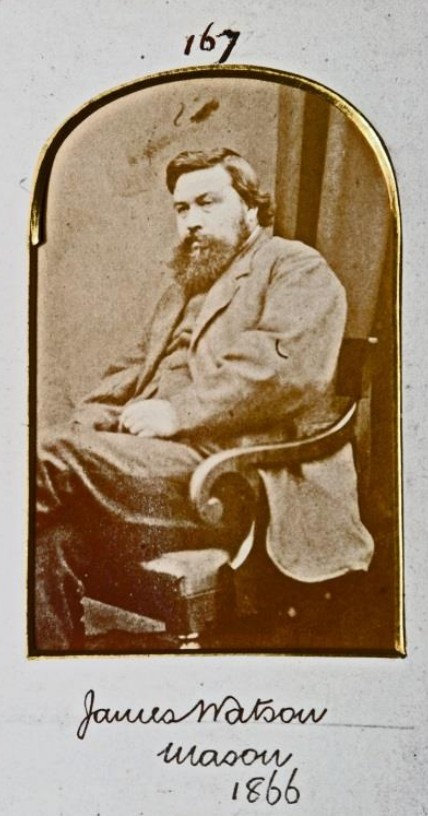

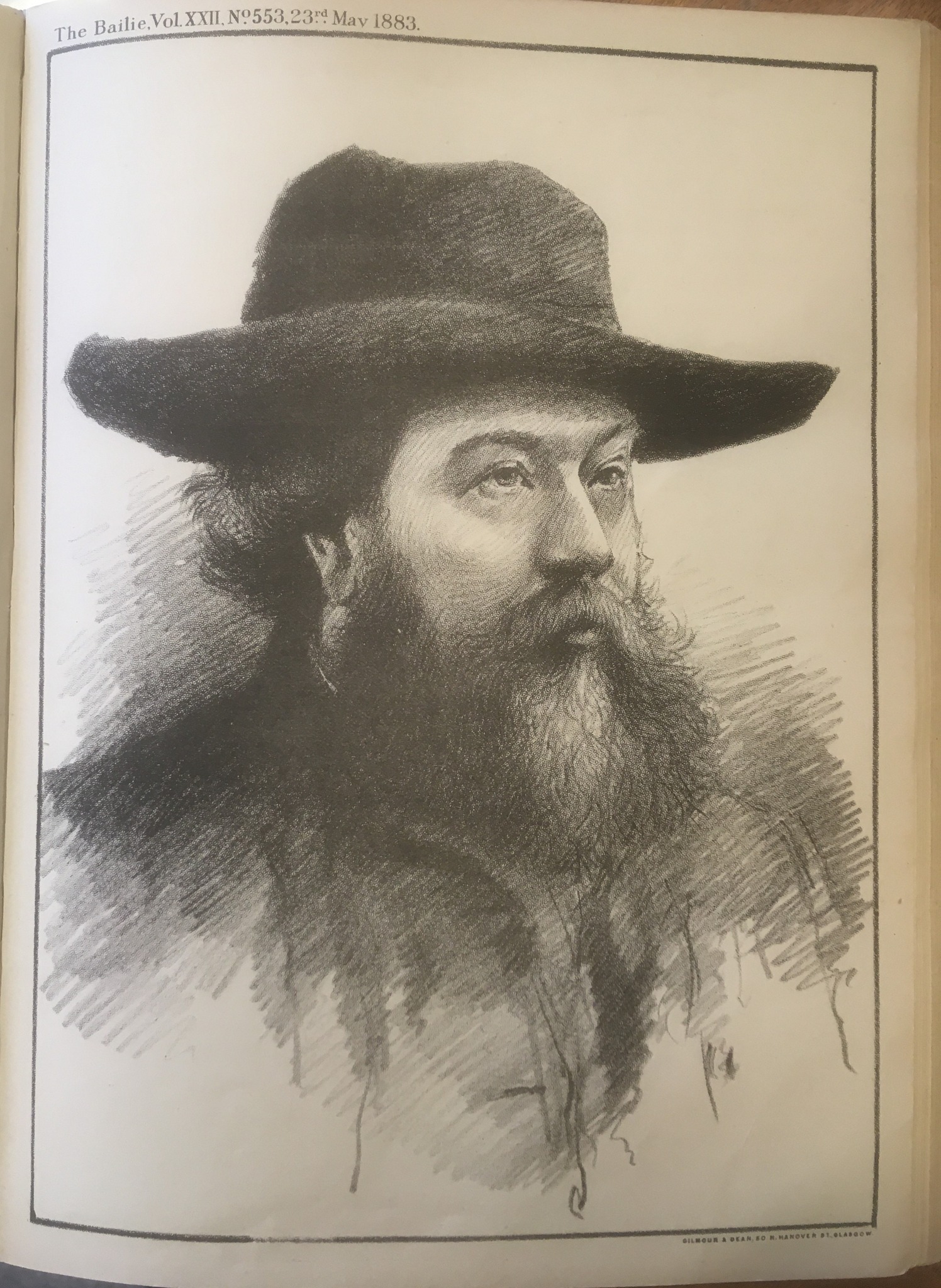

James Watson

In September 1868 the plot for the final Regent Park Terrace tenement (between Marywood Square and Titwood Road) was feued not to William Brown, but to one James Watson. He did however erect his tenement to the same design as the others. Why there was a change in builder is not known.

This appears to have been James “Black” Watson (on account of his hair), a prolific tenement builder in Glasgow who lived in Calton, with offices in Union Street. He was Deacon of the Incorporation of Masons of Glasgow in 1866, taking over from John McIntyre. He died in 1884.

He appeared in The Bailie in 1883, and I hope to find a biography of him there when I can locate a copy.

Francis Armstrong

In June 1876 the land for the fourth terrace on Moray Place was sold to one Francis Armstrong. In the 1885 valuation roll, Franis still owned no 28, and it identifies him as an architect living in Dumfries. The Dictionary of Scottish Architects notes he was born around 1847, the son of Thomas Armstrong, contractor, and his wife Agnes Burgess. He practised as an architect in Dalbeattie in Kirkcudbrightshire in the 1870s and 1880s, and became burgh surveyor of Dumfries by 1911 if not before. He built some churches in the area, but the dictionary only records one Glasgow building, a double villa in Lower Bourtree Drive, Burnside, built about the same time . He died on 24 March 1927 at his home in Dumfries. He had been married twice, first to Catherine Hyslop, and second to Jessie Johnstone Gibson.

It is unusual that the land was feued to an architect rather than a building contractor in this case.

Robert Weir

The north side of Marywood Square was built by Robert Weir in 1877-79. He was a builder based in Allanton Terrace, 1-10 Langside Road, Crosshill. His father William Weir was also involved in the business. It was not a financial success and ended in tragedy.

Alexander Thomson, Brickmaker

Not to be confused with Alexander “Greek” Thomson, the architect. The terrace on the south side of Queen Square was built by Alexander Thomson, brick maker, of 130 Pollokshaws Road, and Robert Anderson, joiner and wright, of Dumbarton Road (now Argyll Street). Thomson subsequently lived for several years in one of the houses he had built, at No. 33 (now 21) Queen Square, as did his son, William .

His brickworks was at Crossbank, Hangingshaw; now underneath the Asda at Toryglen. He was prosecuted for employing under age children there in 1883 .

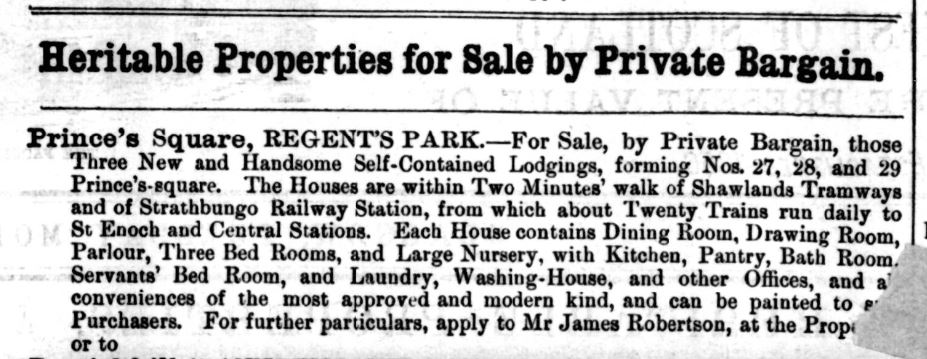

James Robertson

The long terrace on the south side of Marywood Square was built several years after the other sandstone terraces of Strathbungo, possibly due to the financial crisis that followed the 1878 collapse of the City of Glasgow Bank, just as the north side was completed. It was built c.1884-5 and in the 1885 valuation roll the entire terrace was listed as belonging to James Robertson, a mason and builder living in Pollokshields. He first advertised the houses for sale or let in the spring/summer of 1884. Yet in the early 1890s he went bankrupt, and by 1895 the valuation roll notes the entire terrace was then owned by William Stevenson. I have no further information on James – any offers of deeds for review would be gratefully received.

Glasgow Property Circular and West of Scotland Weekly Advertiser, 12 Feb 1884. Source: BNA

Andrew McIntyre

Andrew McIntyre was a builder and brickmaker with a brickworks in Moss side, and the younger brother of John McIntyre, one of the orginal developers of Strathbungo who had lived at Two Moray Place. He inherited the rights to erect a tenement on the north side of Nithsdale Road on the death of his brother, and completed Titwood Place in 1877.

William Howie

William Howie & Sons were the builders of the other Nithsdale Road tenement on the south side of the road, known initially as Matilda Terrace. Little is known of William, although he know he was bankrupted by the failure of the City of Glasgow Bank in 1878, just after completing the tenement, and died two years later. Two sons were also bankrupted and left for a new life in Australia, where they became important contributors to the development of Sydney. The Howies’ story is told in a separate article, William Howie, builder.

John Bennie Wilson

Born in Glasgow, after serving an apprenticeship with John Burnet he set up his own practice in 1879. During this period he designed several churches in the city .

These include, Oatlands United Presbyterian Church (1881, dem.); the competition winning St Albert the Great (formerly Stockwell Free Church), 153 Albert Drive (1886-7); Partick East Church, Milburn Street (1887) the (former) Swedenborgian New Jerusalem Church, 174 Queen’s Drive (1895-7), and the (former) Langside UP Church on Langside Avenue, now St Helen’s RC Church.

His secular buildings include the Headquarters and Drill Hall for the 3rd Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers, 35 Coplaw Street (1884-5). He designed the extension to 1 Moray Place, in the style of the original, and he was living in Strathbungo, at 16 Regent Park Terrace (now 2 Vennard Gardens), in 1888, although he also had a house, Cosiecote, in Dunblane.

He was an enthusiastic volunteer, joining the 3rd Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers as a private in 1868. He was commissioned in 1880 and promoted to Major in 1894 and to Lieutenant Colonel in 1903. He succeeded Colonel Howie as commander in 1905 and marched 700 men past Edward VII at the Edinburgh Review of 1906, but severe illness brought his military career to a close in the following year. He was awarded the Volunteer Decoration .

His other interests included football. He helped form Third Lanark from the volunteer rifles of the same name, played as their striker, and scored their first goal. He was President of the Glasgow Football Charity Cup Committee in 1909. He was a freemason, and member of Kilwinning Mother Lodge.

His son, John Archibald Wilson (1880-1926), trained in his office and later became a partner, as John B. Wilson & Son. Wilson died on 3 January 1923 at 45 Fotheringay Road, and his son died only three years later. After their deaths, the firm was taken over by their former assistant James M. Honeyman, 1929, and continues today as Honeyman, Jack & Robertson.

The Wilsons are buried together in Cathcart Cemetery, their graves marked with a Gothic monument incorporating mosaic and the symbol of the compasses, which identifies Wilson as a Freemason.

Wilson designed the monument for his first wife, Sarah Harrison, who predeceased him in 1896.

John McKissack

John McKissack was a member of the Strathbungo Parish congregation, and designed the second Strathbungo Parish Church, constructed in 1887-8. He also designed the romanesque Queens Park Baptist Church on Queens Drive around the same time .

John McKissack

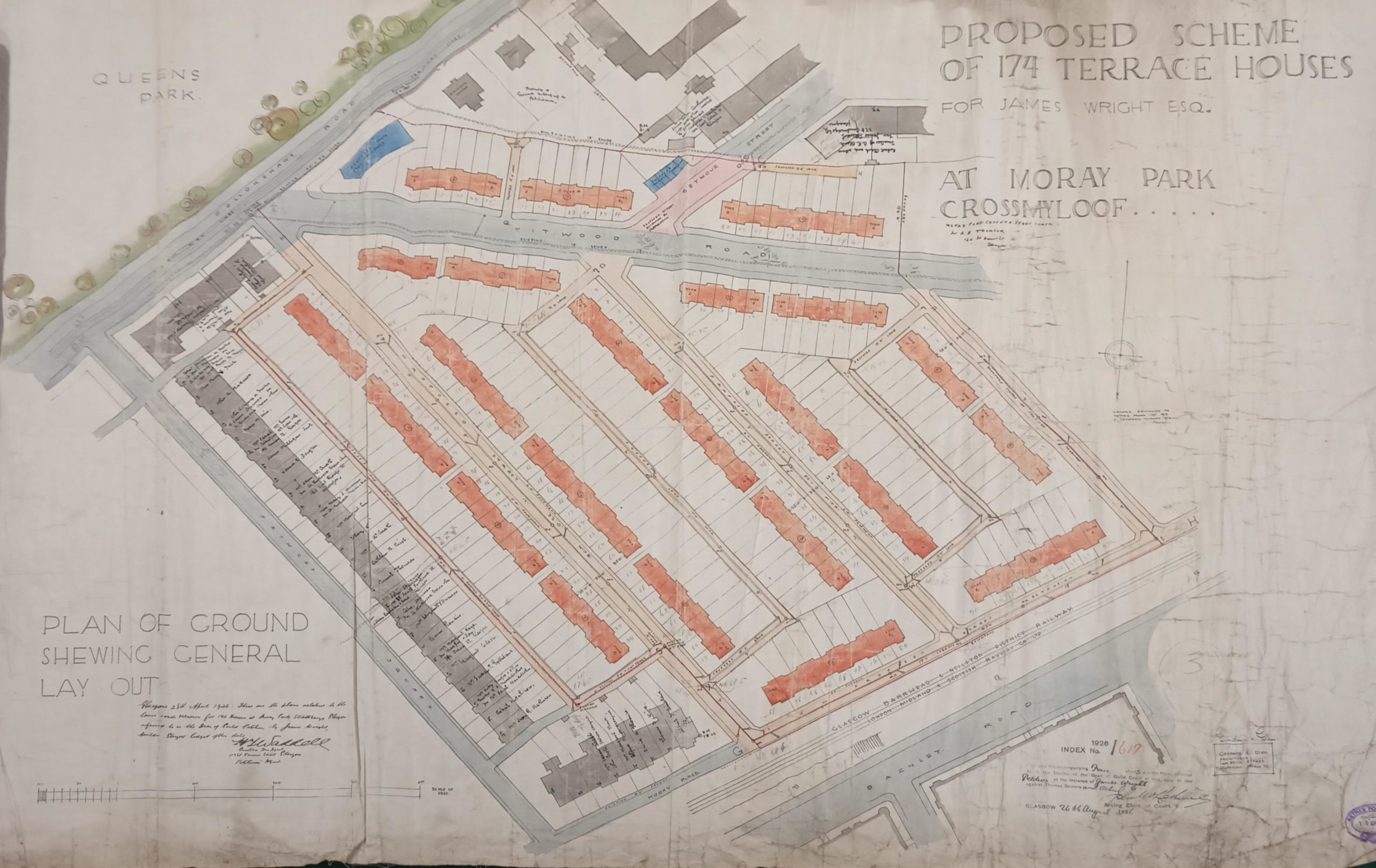

James Wright

James Wright is named on the 1927 feu as purchaser of the land on which the Gardens were built in 1928. He was one of a family of builders, many of whom may have been involved in the construction. He was the son of George Wright and Annie Vennard, who ran a motor hiring business at 60 Tantallon Road (Wright & Low, latterly Whitecraigs Motor Company, but demolished and replaced by flats c. 2005).

James was one of a number of siblings, many of whom were also bricklayers and builders, including George (b. 1876), Thomas (b. 1878), James (b. 1880), Frank (b. 1884), David, Ann & Gavin (b. 1893). Frank had at least five children, including Thomas Vennard Wright (b. 1904) and James Hamilton Wright (b. 1908).

The brothers built the terraced housing in Tantallon Road adjacent to their garage, c. 1925, and in a similar style, also with Gardner & Glen as architects. James was recorded as owner of Rockingham Villa in Kilcreggan (1921). By 1927 Gavin was recorded in a P.O. Directory as living in one of the two villas that originally sat on the site of the current BP garage (Greenhill Cottage, 910 Pollokshaws Road). Gavin had a building office adjacent to his house, in a row of shops on Pollokshaws Road, at the time of the construction of the gardens, but these were replaced in 1937 by the Southern Motor Company’s garage (now McMillan’s restaurant).

Wright Building Office, Pollokshaws Road at Titwood Road, with new Titwood Road housing behind

Southern Motors Garage, Pollokshaws Road at Titwood Road, now McMillan’s, shortly after construction 1937. Source: Glasgow City Archives 8/2465

The roads were originally to be called Moray Place, Vennard Street, Thorncliff Street and Carswell Street, but the names changed to Gardens when constructed (and Thorncliff gained an ‘e’). Vennard was the Wrights’ mother’s name. The origins of Thorncliff(e) and Carswell remain a mystery, although there is a possible link through the masons and the Caldwell family, to the Carswell family. The Carswells were important builders in Victorian Glasgow, erecting many well known buildings in the Merchant City, and the first to build using cast iron pillars. It is also possible the current Caldwell-Wright architectural ironmongery business is descended from the Wright family business – it sits at the back of the BP garage, and hence in the back garden of the Wright’s former homes.

Thomas Vennard Wright, James’ nephew, recalled working on the Gardens. On their completion, Thomas’ next job, in 1930, was the Empire State Building in New York! Some of the family still live in New Jersey, while others remain in Glasgow.

James Wright subsequently purchased Stamperland House in Cathcart, and helped develop the Stamperland and Slaymanshill areas for new housing. James died tragically on 18 February 1933, when his chauffeur collided with a furniture van on the Lockerbie – Annan Road. Stamperland itself was demolished soon after, for further housing development.

James’ son William Moffat Wright founded Southern Motors (Glasgow) and built the car showroom at the corner of Titwood and Pollokshaws Roads in 1937, that now houses McMillans .

(Thanks to Frances Markey, Thomas Vennard Wright’s granddaughter, for information on the family .)

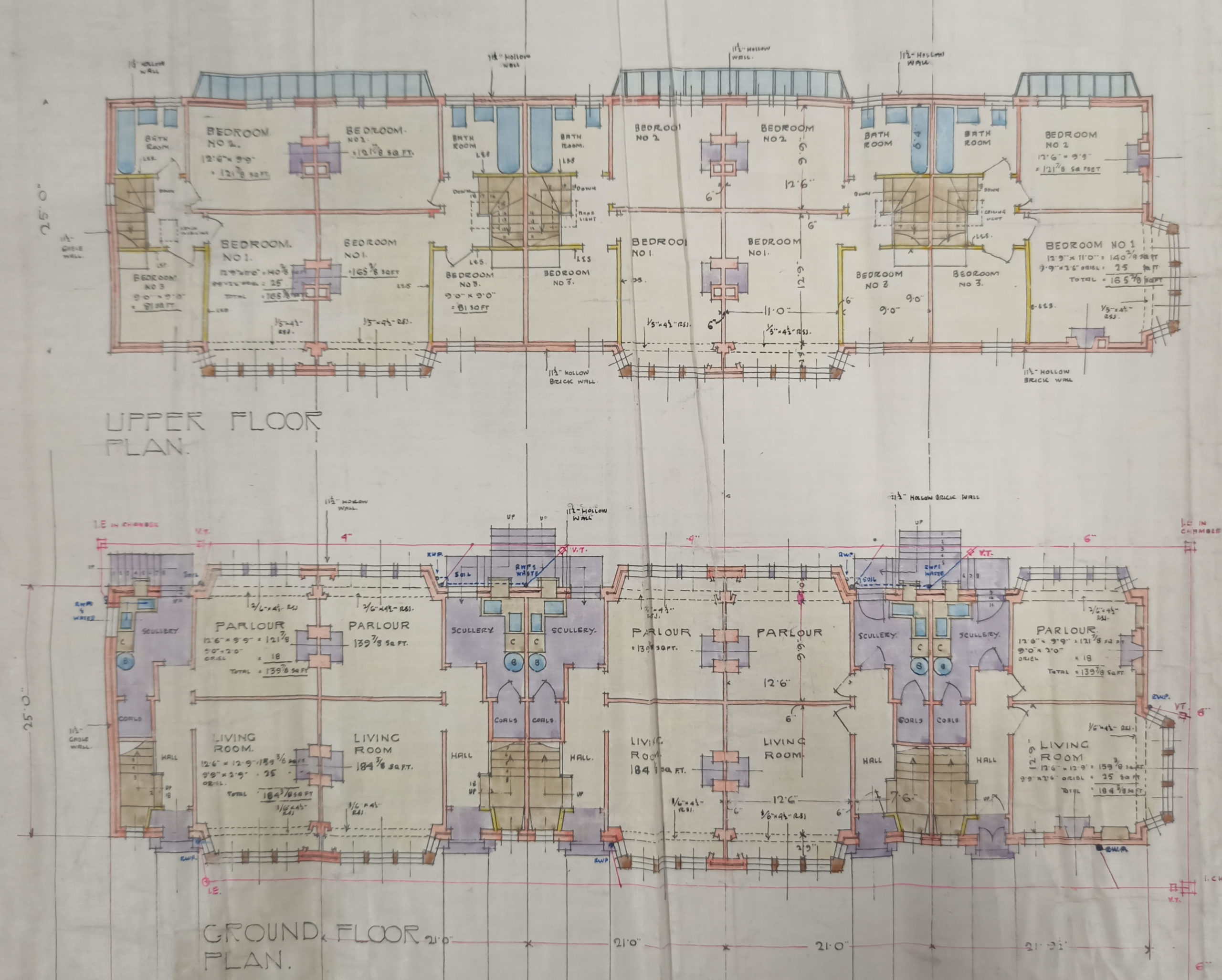

Gardner & Glen

Gardner and Glen were an architect partnership who worked with the Wrights on some southside housing projects, including the Gardens (listed on the deeds as architects) and housing in Tantallon Road. They were, however, much better known for their work on many of the cinemas in the West of Scotland, such as the Grosvenor in Ashton Lane. More details of their work can be found in the Dictionary of Scottish Architects .

Front and rear elevations of the proposed houses for Moray Park, 1926. Gardner & Glen, Architects. Source: GCA

William Todd Aitkenhead

William Todd Aitkenhead was a building contractor who constructed the white houses on the south side of Carswell Gardens. He was the 5th child of Alexander Aitkenhead and his wife Margaret Brownlie Christie Todd.

He was born on 29 September 1886 at South Street, Greenock, married Margaret Maitland Mason in Glasgow in 1921, lived in Maxwell Avenue, Westerton, and died in Glasgow on 13 April 1934, at 121 Hill Street (then possibly a nursing home, now part of the School of Art) at the age of 47.

R. Aitkenhead & Son of Greenock were an offshoot of a large family of stonemasons from Blantyre, Lanarkshire, who had been building bridges and other structures in the Hamilton and Bothwell area since the late 18th century. The Greenock branch was founded by Alexander Aitkenhead (1858–1933). He had trained as an apprentice in the firm and spent two years further training in North America in the late 1870s.

In 1882–3 the company had erected Mure Memorial Church, Baillieston, and Girvan Parish Church, and one of Alexander’s first jobs on returning to Scotland was as foreman for another new church, in Blantyre. He moved to Greenock in 1883 to supervise construction of Finnart United Presbyterian Church, and opened new offices in South Street.

Alexander won contracts for Tarbert Parish Church, Kintyre (1885–6) and Dunoon Sheriff Court (1899–1900), both by John McKissack, and for J. J.

Burnet’s Gardner Memorial Church, Brechin (1897–8). He enlarged the ‘splendid palace’ of Balinakill House, Kintyre for shipowner and philanthropist Sir William MacKinnon in the early 1890s, and erected over 30 villas in the wealthy enclave of Kilmacolm, where Honeyman, Keppie & Mackintosh had several clients.

R. Aitkenhead & Son became major contractors to the War Office, including masonry and sub-sea defences at Fort Matilda in Greenock, fortification work at Inchkeith on the Firth of Forth, and massive concrete gun batteries at Portkil, Kilcreggan (1900–1) and Ardshallow on the Clyde. These were ‘hidden, sheltered, protected by heavy earthworks’, and contained long-range guns – a complete contrast to the new St Lawrence’s Catholic Church in Greenock, ‘so delicately wrought’.

For industrial clients Aitkenhead’s made the concrete bases for the Scottish Aluminium Co.’s heavy machinery, laid the concrete floors of local shipyards to withstand the pressure of keels under construction, and extended Ardgowan Distillery.

The Aitkenhead partners changed over time. In 1896, both branches were reorganised, and Alexander and his younger brother Andrew (1869–1910) became sole proprietors at Greenock, where they moved to Trafalgar Street. Other family members joined them around 1911, including Robert Aitkenhead (Alexander’s son, 1881–1958), who was one of two architects in the family at the time with the same name.

(Thanks to Pamela Harrow and Robert Aitkenhead for biographical details).

April 9, 2020 at 2:04 pm

Fantastic information. Thanks very much. Refer back to the site often.

September 3, 2020 at 12:05 pm

Carswell, Robert, joiner and cabinet maker pollokshaws directory

https://digital.nls.uk/directories/browse/archive/85939596?mode=transcription

Just found this very interesting u may have it

http://clark-debisschop.co.uk/tng/getperson.php?personID=I6551&tree=Clark

Frances Wright/Vennard

October 3, 2024 at 1:34 pm

to Frances Wright/Vennard,

I am a speaker and I will be very grateful for any information on the Vennards especially Annie your maternal grandmother and her parents background. It will be used as a little bit of info. on my Talk of “The Queer Folks of the Shaws”. which is a Huguenot Story with local poets, and the Vennards were Huguenots. I loved the background info on the building of Vennard Gardens from the “bungo blog” I daresay we may be relatives through the Vennard line many times removed. I look forward to any further info you can glean on the matter and enhance my talk.

many thanks

David Vennard