The village of Strathbungo was a small rural hamlet consisting of coal miners, weavers, flower growers, and a number of public houses, up until the major urban expansion of Glasgow and its suburbs circa 1850-60.

The village in the early 19th Century

The best accounts of early Strathbungo are probably found in Alexander Scott’s articles for the Archaeologcal Society of Glasgow, Notes on the Village of Strathbungo , and An Account of the Kinninghouse Burn . Although written in the 1880s, he spoke to many elderly locals to produce an account of the village in earlier times.

Map of Pollok Estate excerpt. Robert Ogilvy. 1741

Robert Ogilvy’s map of 1741 is the first detailed record of the village. It shows buildings all along the west side of the main road to Pollokshaws, from the boundary with the Gorbals in the north down to the Crosshill Burn in the south, named as Marchtoun. Plots of land include North Cammeron, north of the present Nithsdale Street, and two smaller plots behind it across the Kinninghouse Burn. South Cammeron is to the south of Nithsdale Street, west of Pollokshaws Road, and bounded by the two burns west and south.

On the east side of Pollokshaws Road, north of Allison Street are two plots, a smaller one to the north, bounding onto Gorbals, where the converted former Strathbungo Parish Church now stands. The more southerly is larger, extending further east. South of Allison Street is Spittal Croft, the name suggesting the existence in pre-Reformation times of an old hospital or almshouse. The first residents were likely crofters on these plots, perhaps attracted by the hospital. The Cammeron plots are also named as Cammeron’s Eye on the plan’s index, and a part of the Gorbals moor immediately to the north Sievewright & Cammeron’s Eye on another plan. Coal was just below the surface in Strathbungo, and there were many small coal pits in the area. The old practice of mining coal by digging more or less horizontally into exposed coal seams was known in Scotland as the “In-gaun-ee” (In-going eye) system, and the names may relate to mining activity in the village. When the railway cutting was dug in the 1840s, the coal seams were also exposed there.

One of the earliest of the village feu-rights is a Feu-Charter dated 7th October, 1727, granted by “Sir John Maxwell of Nether Pollok, Baronet, one of the Senators of the College of Justice,” to “Andrew Shiells, maltman, second lawful son of the deceased John Shiells in Titwood.” By this Charter, there were conveyed to the feuar,

“All and haill one rood of land lying upon the west side of the publick highway leading from Glasgow to Pollockshaws, bounded by the town of Glasgow’s march on the north, the said highway on the east, and the lands of Titwood called Cameronseye upon the south and west parts, as the same is already meithed and marched; and All and haill one other rood of land upon the east side of the highway foresaid directly opposite to the rood above-mentioned, bounded by the town of Glasgow’s march on the north, the lands of Titwood on the east and south, and the foresaid highway upon the west parts, as the same is already meithed and marched; lying within the parioch of Govan and Sheriffdom of Renfrew.”

This would refer to buildings on the west side of the main road, north of Nithsdale Street, possibly for a public house, a maltman being a brewer. There was later Granny McDougall’s Inn, also known as the Robert Burns Tavern, on this site, and following demolition c 1895, new tenements, and now Kelly’s Bar. Andrew Shiells’ father was John Shiells, the farmer at Titwood Farm. Several of the name Schiellis fought with John Maxwell at the battle of Langside, and it may be the family had been on Maxwell land for centuries, and took their name from the land.

The feus of this period also mention William Neilson, thatcher in Strathbungo, and Houston of Jordanhill, and Dunlop of Garnkirk, who sold their land on the east side of the road in 1790 to John Wallace, shoemaker in Marchtown. David Muir, collier in Marchton, purchased part of Spittal Croft in 1773. Further sales on the east side were to James Ross, collier at Marchton, and later David Neilson, weaver at Marchton (1800).

A separate account, an encyclopaedia of 1841, records metal files being manufactured in Strathbungo in 1766, a very early record of ironmongery and metal manufacture in Scotland .

Scott details some of the coal mining activity in Strathbungo , including that of James Ross, who rediscovered an old pit entrance in his back garden, and set about reopening it, and selling the remaining coal he found there. This prompted his neighbour to dig his own pit, but found it full of water and the coal gone, leading to a dispute with his neighbour, who he suspected of removing it. All this took place roughly under what is now Nicola Sturgeon’s parliamentary office, though I doubt she is aware of it.

He describes the oldest remaining houses as a thatched row on Pollokshaws Road, north of Nithsdale Street, although a footnote states they were bought back by the Maxwells of Pollok with a view to broadening the approach to Pollokshields, but when Nithsdale Drive was laid out by the city and the Maxwells, this became unnecessary. The properties were demolished anyway in June 1885, replaced by red sandstone tenements.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw a boom in weaving, and there was a large population of weavers in the village, with just about every house contained a loom-shop. The quality of work produced increased when John Houston, a weaver from Paisley, settled in the village in the late 18th century, and introduced weaving of harness plaids (similar to a kilt) and other fancy work. His son William, also a weaver, later worked for Neale Thomson of Camphill in his cotton business. It is estimated there were 80 weavers in the village at this time. Hand weaving fell victim to industrialisation and income dropped. Scott estimated the last loom in Strathbungo was lost in the 1880s, and many of the older population fell into poverty. He describes one seeking help from the parish “I was born in the Shaws; but I cam to Strabungo the nicht o’ my marriage; and I’ve aye lived there since till I cam to Glasgow after my auld man deed. I need to get something noo frae the parish.”

Scott recalls a game of shinty played beside the burn in the early 1800s between teams from Strathbungo and Cathcart (opposite sides of the burn), where at least one team member was pushed in for a soaking. Boys were employed as herders in the local farms, before being apprenticed to the loom, while lasses worked as servants in the farm houses. They contributed to bringing in the harvest, and would rent a small plot for vegetable growing.

Schooling

Strathbungo had a school with a good reputation in the neighbourhood. It was originally on the east side of the village.

It was a very primitive building, and the thatched roof was so worn that every rainy day made the clay floor a perfect mess. This deficiency of comfort, however, furnished a much-relished kind of mischief to the boys. Holes were surreptitiously made in the soft floor with a stick, and as these filled with rain the water was squirted up into the face or neck of some unfortunate boy. Mr. Auld, who afterwards became a minister in Greenock, was then the master. He did not believe in laying out money upon the upkeep of the school; and during “vacance,” certain of the boys had to attend to repair the floor. There were usually about fifty children attending Mr. Auld’s school. The school was afterwards held in the loomshop in Park’s property on the west side next Glasgow; but it was for sometime in a building now removed, situated in the north-west corner of the Queen’s Park lands. Its next locus was in a barn adjoining the present smithy. Its subsequent quarters were two rooms of the upper storey of William Houstoun’s house, and latterly a school house (the Govan Sessional School) was specially built where March Street is now. In this school house the village band, which was started ten years ago [c.1875], used to practice.

The school can be seen in its March Street location on the 1858 OS Map. It was built c 1840, and continued its use until School Boards were set up in 1873 and education was no longer the responsibility of the church .

Public Houses

Strathbungo had a bit of a reputation for its public houses, a trend that continues to this day. The Cross Keys Tavern (landlord George Mathieson, 1861) was north of the crossroads, on the west side opposite the church. Granny (Janet) McDougall’s Burns Tavern was on the north west corner of the crossroads in “that ruinous building”, that closed c.1870. The site is shown below in 1890, the north west corner on the right. An OS Map surveyed in 1894 shows the old buildings still in existence here, so the plumber’s may or may not be the building in question. The building was demolished in 1896.

Strathbungo 1890s, from Allison Street, Strathbungo Station in the far distance

The Hunter’s Inn was on the south east corner, and another pub on the west side was represented by a game of curling on its board (the “Curler’s Inn”). The 1861 PO directory also lists the Queen’s Park, run by Malcolm Findlay. The park itself was being laid out at the time.

Church

The village was in Govan parish, which meant a long trek to church on a Sunday. There was already a chapel of ease in the Gorbals by 1732, but it was only in 1833 that a mission station was set up in Strathbungo, probably in the school. After fundraising, Strathbungo’s first church was built in 1839-40, immediately north of the village, on land provided by Hutcheson’s Hospital. This small church was designed by Charles Wilson, and cost £1300. It is on the left in the painting of old Strathbungo that sits atop this article.

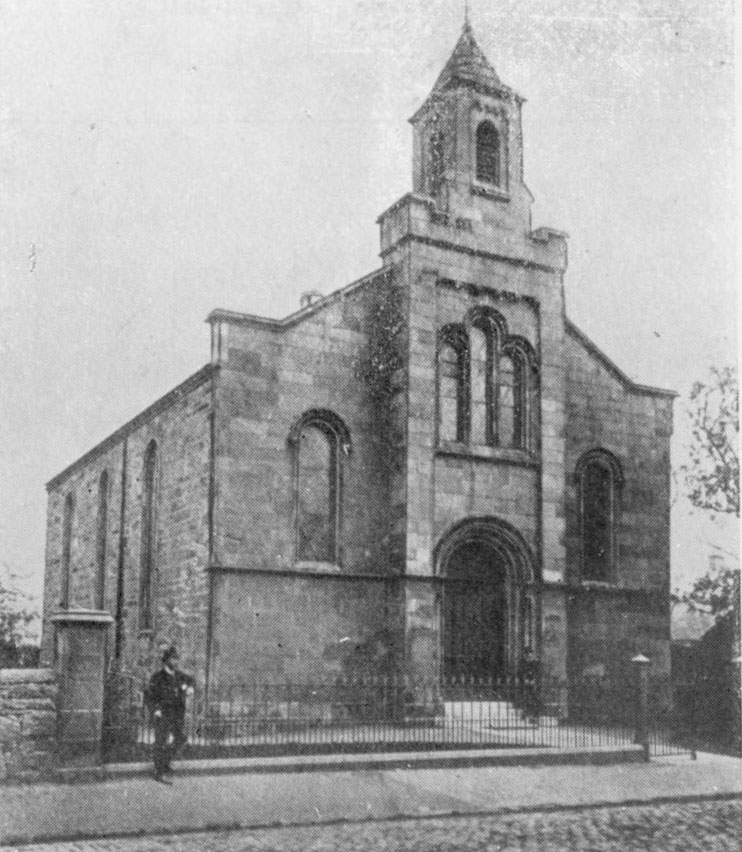

Old Strathbungo Parish Church

The church was modified in 1876 but still proved too small, and was knocked down and rebuilt in 1887-88. The new church itself is now closed, and more recently was redeveloped into flats, although the tower and frontage on Pollokshaws Road have been retained.

The land to the south west of the village was cut off from Maxwell’s farm land of Titwood with the coming of the railway in the 1840s, but remained agricultural apart from A & T Hamilton’s Titwood Brick and Tile works, which sat approximately half way down the Queen Square/Marywood Square back lane. The original feu disposition of 1860 between Sir John Maxwell, and William Stevenson & John McIntyre for the building of modern Strathbungo refers to compensation to be paid to Alexander Hamilton, brickmaker in Glasgow and Thomas Hamilton, brick and tile maker, Auchingray Brick and Tile Works, Carnwrath, since they would be required to vacate the site, although the business remained until dissolved in June 1862.

In the mid 1860s, when this building was proceeding apace, Cathcart Parish attempted to claim the new terraces on Pollokshaws Road as its own, claiming its land extended to the burn, but Govan Parish won out, and the two parishes looked across at one another across the main road, from Bute Terrace (e.g. Shimla Pinks, now Brodies) in Cathcart, and Regents Park Terrace in Govan.

Thus between 1860 and 1900 Strathbungo was changed beyond all recognition, and the rural village was gone forever.

Strathbungo in the 1850s

A description of the village can be found in Hugh MacDonald’s Rambles Round Glasgow , first published in 1854. He isn’t too impressed as he passes through on his journey to Pollokshaws.

Crossing the Clyde by the elegant and spacious Broomielaw bridge, and passing along Bridge Street, Eglinton Street, and past the front of the Cavalry Barracks, now deserted by its gay cavaliers, [*Since this was written, the establishment has been converted Into the Poorhouse of the Govan Parish.] we soon arrive outside the boundaries of the city. A walk of a mile or so farther — during which we pass on the right, Muirhouses, a row of one-storeyed and thatched edifices, and at a short distance to the left, the hamlet of Butterbiggins — brings us to a little village which rejoices in the somewhat unmusical appellation of Strathbungo. There is nothing particularly attractive or worthy of attention about this tiny little congregation of houses.

He notes the parish church, a “small, neat and plain specimen”, which was built in 1839, but later replaced in 1878, and the multiple public houses, including the Burns Tavern, which was adorned with a less than flattering portrait of Burns, stating of the artist

Want of will or want of power has given him the solitary merit of being an absolute stranger to flattery.

Nonetheless Scott in his later account noted the fame of Burn’s portrait, noting that someone made off with it.

The village itself consists of:

for the most part humble one or two-storeyed buildings, inhabited principally by weavers, miners, and other descriptions of operatives.

He also notes one of Strathbungo’s earliest heroines, quoting a song by Adam Knox from Whitelaw’s Book of Scottish Song (1844) . Here’s the full version of Strathbungo Jean, to be sung to the tune of “Andro and his Cutty Gun” . Quite. If you wan’t to have a go, there’s also a live version of the tune on YouTube .

BLYTHE, blythe could I be wi’ her,

Happy baith at morn and e’en,

To my breast I’d warmly press her,

Charming maid, Strathbungo Jean.The Glasgow lasses dress fu’ braw.

And country girls gang neat and clean,

But nane o’ them’s a match ava

To my sweet maid, Strathbungo Jean.Though they be dress’d in rich attire,

In silk brocade and mos-de-laine,

Wi’ busk and pad and satin stays,

They’ll never ding Strathbungo Jean.Bedeck’d in striped gown and coat,

Silk handkerchief and apron clean,

Cheerfully tripping to her work,

Ilk day I meet Strathbungo Jean.Ye gods who rule men’s destinies,

I humbly pray you’ll me befrien’,

And aid me in my dearest wish

To gain my sweet Strathbungo Jean.Gi’e to the ambitious priest a kirk,

Gi’e riches to the miser mean,

Let the coquette new conquests make,

But, O! gi’e me Strathbungo Jean!No happiness all day have I,

My senses are bewilder’d clean,

In bed all night on her I cry,

My heav’n on earth, Strathbungo Jean.Should fortune kindly make her mine,

I would not change for Britain’s queen;

But fondly in my arms I’d clasp

My charming maid, Strathbungo Jean.

Mr MacDonald also remarks upon the horticultural skills of the locals.

A considerable number of the humble edifices, however, have garden-plots attached to them for the cultivation of kitchen vegetables; and it is well known that both here [Crossmyloof] and at Strathbungo many of the handloom weavers are celebrated growers of tulips, pansies, dahlias, and other floricultural favourites. Florist clubs, also, exist among them, which meet regularly for the examination of choice flowers, and for discussing the best means of rearing them to perfection. We have had the pleasure, at various periods, of conversing with several of these bloom worshippers—for such, in truth, they are—and we must admit that we were fairly astounded at the multifarious charms which they could discover and point out in what seemed to our obtuse visual organs a simple tulip or pansy….most assuredly, for seeing into the mysteries of a tulip or a dahlia, we shall back a Crossmyloof or Strabungo weaver against the united amateurs of Scotland.

Whether these skills were related to the presence of the large Austin & McAslan nursery on the north side of Strathbungo village is unclear; it had been present some 25 years before he wrote his description.

Leaving Strathbungo he goes on to describe the ancient British camp atop the hill in what would later become Queens Park, Mr Neale Thomson’s fine house at Camphill (now private flats, next to the 5-a-side pitches in the Park), and the huge bakery run by Mr Thomson, “perhaps the largest in the queen’s dominions”, which was Glasgow’s main source of bread, producing 40,000 quartern (4lb) loaves a week. The bakeries were on the site of the industrial units between Pollokshaws Road (the Glad Cafe, etc) and Waverley Street, and not as one might assume, on nearby Baker Street. That was the location of Thomson’s cottages for his workforce, designed by Alexander “Greek” Thomson.

Leave a Reply